Thomas Patrick Ashe (1885–1917) was born on January 12, 1885 at Lispole, near Dingle, County Kerry. He was the fourth son in a family of seven boys and three girls born to Gregory Ashe, a farmer, and Ellen Hanafin.

Both Irish and English were spoken in the Ashe home. Thomas’s father was an Irish scholar, storyteller and singer. Learners of Irish used to come to listen to his stories.

Thomas attended Ardamore National School (1889–1900), where he was a promising student, winning two county scholarships. He joined the Gaelic League while at school, becoming a local organizer. He was also active in the Lispole Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA).

Ashe trained to be a teacher at De La Salle College, Waterford (1905–7), where he again excelled. After briefly teaching at Minard Castle National School, County Kerry (July 1907 to March 1908), he became a master at Corduff National School, near Lusk, in north County Dublin (March 1908 to April 1916).As a teacher and as school principal he was both efficient and popular, but his tendency to press his political nationalism upon his pupils often brought disapproval from government school inspectors.

Irish Republican Brotherhood

Ashe joined the IRB in the spring of 1913. He regularly met other leading members, including Seán MacDermott and Diarmuid O’Hegarty, and in November 1913 he became a founding member of the Irish Volunteers. Locally, Ashe played a leading role in forming the Black Raven Pipe Band in 1910. The Black Raven won the championship of Ireland at the Oireachtas (pron: oh-rock-tus) in Galway in 1913.

Historian Peter Hart noted, “Ashe was a gentle, devout and much loved man, cut from the same idealistic cloth as Patrick Pearse and Joseph Plunkett.”

From February until the summer of 1914 Ashe took leave from his job and travelled to the USA, where he collected money for the Gaelic League and (secretly) for the IRB. Sometime between October 1915 and the outbreak of the 1916 Rising, Ashe became commandant of the 5th (Fingal) Battalion of the Irish Volunteers, which ultimate formed part of the Dublin brigade.

Easter Rising

Commanding the Fingal Battalion of the Irish Volunteers, Ashe took part in the 1916 Easter Rising. Ashe’s force of 60-70 men engaged British forces around north County Dublin during the rising.

The battalion won a major victory in Ashbourne, County Meath, where they engaged a much larger force capturing a significant quantity of arms and 20 Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) vehicles. This group also successfully demolished the Great Northern Railway Bridge, disrupting access to the capital.

Twenty four hours after the rising collapsed, Ashe’s battalion surrendered. On May 8, 1916, Ashe was court-martialed and was sentenced to death. The sentence was commuted to penal servitude for life.

On June 20, 1917, four thousand people welcomed Ashe back to Tralee, County Kerry. He was by then serving as president of the Supreme Council of the IRB. Ashe embarked on a series of meetings and speeches, reorganizing the Irish Volunteers and promoting the republican cause.

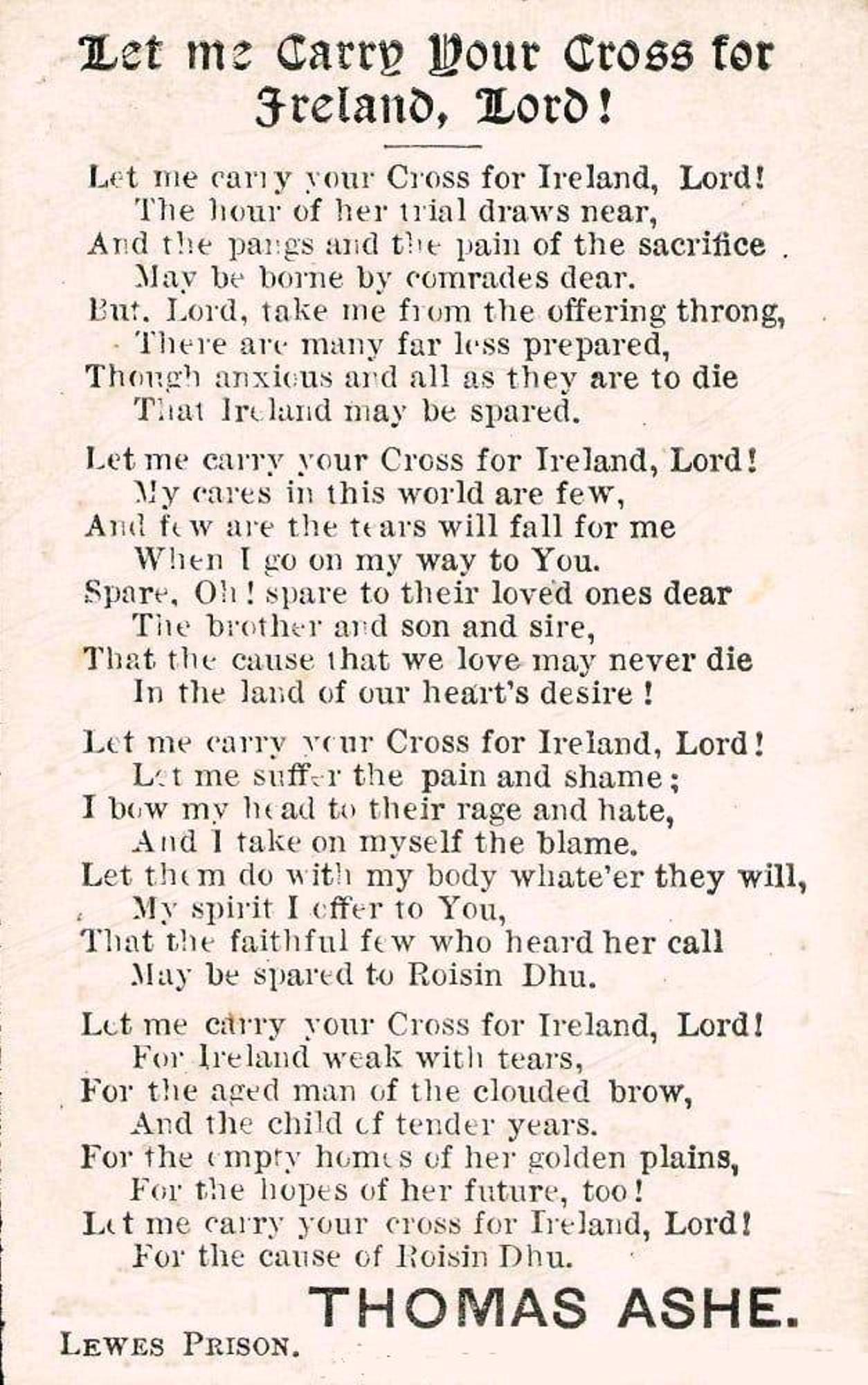

Ashe was imprisoned in Dartmoor prison and then at Lewes Prison in England. While at Lewes, he was in regular communication with Michael Collins and so was better informed about developments in Ireland than many of his fellow prisoners. It was at Lewes Prison that Ashe penned his famous poem titled, Let Me Carry Your Cross for Ireland, Lord!

At Lewes, Ashe and Thomas Hunter led a prisoner hunger strike, which began on May 28, 1917. With accounts of prison mistreatment appearing in the Irish press, Ashe and the remaining prisoners were freed on June 18, 1917 by Prime Minister Lloyd George, as part of a general amnesty.

On June 20, 1917, four thousand people welcomed Ashe back to Tralee, County Kerry. He was by then serving as president of the Supreme Council of the IRB. Ashe embarked on a series of meetings and speeches, reorganizing the Irish Volunteers and promoting the republican cause.

Defense of the Realm Act (DORA)

A July 25, 1917 speech, in Ballinalee, County Longford, brought about his re-arrest in Dublin and he was prosecuted under the DORA. He was sentenced to two years’ imprisonment. In Mountjoy Jail he was among forty DORA prisoners who began a protest against their treatment, demanding “political prisoner” or “prisoner of war” status.

The prisoners initiated a hunger strike on September 20, 1917. As this was a breach of prison discipline, the authorities retaliated by taking away the prisoner’s beds, bedding and boots. After 50 hours lying on a cold stone floor, the prisoners were subjected to force feeding.

On September 23rd and 24th, Dr. Raymond Dowdall, the prison medical officer, force fed Ashe. On the morning of September 25, 1917, the same operation was carried out by Dr. William Lowe, who was unfamiliar with the procedure.

Immediately after the feeding, Ashe collapsed. He was transferred to Mater Misericordiae Hospital (also known as the Mater Hospital), where he died later that evening.

On September 27, 1917, a coroner’s inquest was held to investigate the death of Ashe. The jury condemned the staff at the prison for the “inhuman, dangerous and unskillful operation performed on the prisoner, and other acts of unfeeling and barbaric conduct.”

They concluded that Ashe had died of heart failure and congestion of the lungs, and that this was due to force-feeding, combined with the previous removal of his bedding and boots (which had left him in a physically weakened state).

In the words of Michael Collins, “The death of Tom Ashe has filled everybody, even political opponents, with horror and indignation, but a day of reckoning will come.”

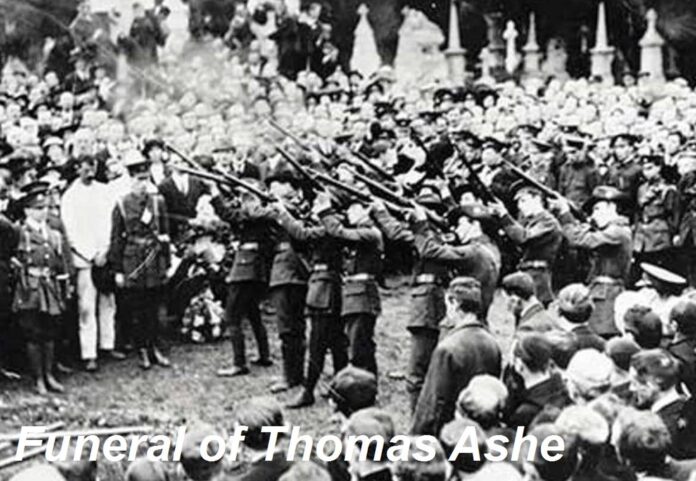

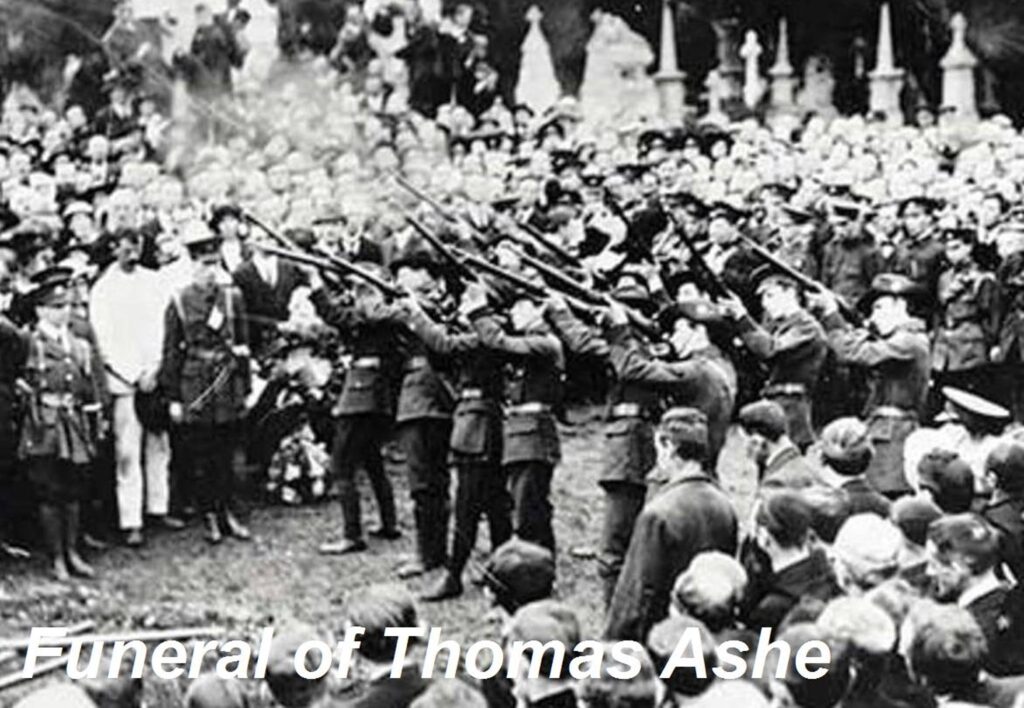

The funeral services for Ashe were organized by the IRB (using a cover name the Wolf Tone Memorial Society) and the Dublin brigade of the Irish Volunteers. Richard Mulcahy was in charge of the arrangements. Michael Collins was designated to deliver the graveside oration.

Thomas Ashe’s body was taken to the Pro-Cathedral on Marlborough Street for a solemn Requiem Mass on Thursday, September 27, 1917, and from there, to the City Hall to lie in state until the day of his funeral. An armed guard of uniformed Irish Volunteers kept vigil as thousands came to pay their respects and offer a prayer for his soul.

On Sunday, September 30, 1917, after lying in state at Dublin City Hall, Ashe’s cortege made its way through Dublin to Glasnevin Cemetery, where he was buried. An estimated 40,000 people lined the route.

At the graveside, twelve uniformed Volunteers fired a volley of three shots and then Michael Collins stepped forward and made a short and revealing oration in English and Irish. His words were: “Nothing additional remains to be said. That volley which we have just heard is the only speech which it is proper to make above the grave of a dead Fenian,” leaving the Irish population in no doubt what was needed to gain independence from England.