More than twenty years ago, I travelled to Northern Ireland as a faculty member in John Carroll University’s first Northern Ireland Peacebuilding Institute. I had taken a course earlier at the University of Ulster – Coleraine, which explored the complexities of the Northern Ireland conflict as part of British imperial history and where I was introduced to a volume of three essays, Nationalism, Colonialism, and Literature, written by the great scholars, Frederic Jamison, Edward Said, and Terry Eagleton.

Originally published as individual pamphlets by the Field Day Group, these essays were significant for the kind of analysis which interpolates literature into history and history into literature. The Institute’s goal was helping students to grasp the historical past as well as the present moment. We wanted them to understand Ireland’s colonial history from far before Michael Collins signed the Anglo-Irish Treaty, and to see how this history shaped what it means to live in a country where the minority population – the Catholics – faced systemic civil rights oppression and constant economic deprivation.

Bloody Sunday was the scandalous image of the Conflict, but life in Divis Flats or detention by the then RUC were the daily realities. During our five weeks there, we met with the partisan leaders, John Hume, Ian Paisley, Gerry Adams, and Martin Mansergh, but we also visited the segregated neighborhoods, and the “interface areas,” of Belfast and travelled to Stroke City, as Derry was then called. We saw the bomb sites and the murals, walked through Long Kesh Prison, attended an IRA funeral, and heard Francis Black sing rebels’ anthems.

In addition to reading histories and political analyses, and listening to politicians and community leaders, we thought about the role that culture plays in conflict and in peacebuilding. I am sure that every student from that trip remembers two such cultural acts we witnessed in Belfast on July 11 and 12, the height of The Marching Season.

On the night of July 11, we saw huge bonfires built perilously close to buildings whose roofs they reached. Atop the blaze were images of Gerry Adams, Martin McGuiness, and other Republicans (or from their perspectives, terrorists) being burnt in effigy while Protestants sang, drank, and cheered.

The next day, we watched the Orange Order Parades. I recall my students looking a bit stunned at the mixture of old men in back suits, bowler hats and orange sashes and at the young men, shirtless, but abundantly tattooed with the date 1690 and the image of a King (King Billy or William of Orange) large across their backs.

Grannies and children sat curbside on folding chairs, wrapped in Union Jack towels or shaded by Union Jack umbrellas. Each pipe and drum band had its own tall majorette and local chapter banner.

We felt the vibe: an in-your-face assertion of Protestant identity, domineering and triumphant. As Seamus Heaney wrote in “Orange Drums, Tyrone, 1966” the drummers were simultaneously ridiculous and menacing:

“The Lambeg balloons at his belly, weighs/Him back on his haunches, lodging thunder/Grossly there between his chin and his knees./He is raised up by what he buckles under.”

Later we discussed the parade’s iconography and tone. Emblazoned on t-shirts, banners, or arms and torsos, the 1690 date proclaimed the Protestant ascendancy from the Battle of the Boyne, when William of Orange soundly defeated Catholic King James II after stripping him from the throne during the Glorious Revolution.

In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the English endeavored to displace or control the native Gaelic population through establishing the Ulster plantations. Tracts of land in Armagh, Cavan, Fermanagh, Tyrone, Donegal, and Londonderry were seized and re-distributed to the new owners, and landowners were required to speak English, have loyalty to the King, and be Protestant.

The colonization was successful as Ulster, once one of the most Catholic of the four counties, became largely Protestant. The further imposition of Penal laws well into the eighteenth century deepened Irish Catholic resentment and rebellion.

For Edward Burke, the penal laws were an elaborate machinery, “well fitted for the oppression, impoverishment and degradation of a people, and the debasement in them of human nature itself.” Among other prohibitions, the penal laws barred Catholics from political activity, exiled Catholic bishops, suppressed the teaching of religion in schools, and enacted ways to cede land to Protestant relatives of Catholic owners. (https://www.praoh.org/history/Articles/PenalLaws5_08.pdf).

This brutal history was the deeper past of the violence in Northern Ireland and to a Catholic, every marching Orangeman embodied civil rights violations in an increasingly militarized society. It was not my job as an instructor in this course to be an apologist for Irish Republican activities, however much I am descended from an IRB member, and the students were likewise required to produce analyses that were objective, cogent, and evidence based.

To this end, we visited community centers where Protestant workers and their families gathered, impoverished and afraid of the spiraling violence in their neighborhoods. And we listened to spokespeople along the entire spectrum of Northern Irish politics from the UUP to Sein Féin, with the DUP and SDLP in the more moderate middle.

We read about the interplay of colonialism, nationalism, and civil rights violations, seeing how a shift in even one of those perspectives would alter analyses. And we debated how invested Great Britain was in keeping Northern Ireland intact for all of its citizens.

And of course, we read literature. The literature of the Northern Ireland conflict speaks from every perspective, from that of race, employment, and locale, and it numbers among its writers the Field Day Group, with novelist Seamus Deane, poet Tom Paulin, playwright Brian Friel and the great Seamus Heaney.

Were I pressed to recommend a single short story as a window into life in the mixed or interface areas, it would be Mary Beckett’s, “A Belfast Woman.” Kenneth Branagh’s film, Belfast, offers another accurate view.

But it is the poets’ voices that provide whatever instruction can be had from such (as Seamus Heaney put it) “intimate revenge.” Derek Mahon, Paul Muldoon, Sinead Morrissey, Medbh McGuckian, Michael Longley, and Ciaran Carson all describe the heartbreak of knowing a person from across the divide who died in the crossfire.[i]

Here is one especially beautiful poem by Michael Longley, the Belfast writer who died just this past January. He spent much of his time in Carrigskeewaun, County Mayo.

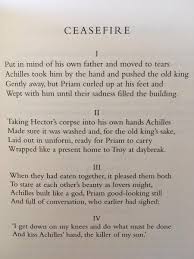

Longley studied Classics at Trinity College and rewrote the famous encounter in the Illiad where Priam visits Achilles to retrieve the body of his dead son, Hector, whom the general had slain. In his sonnet, “Ceasefire,” Longley replaces the men’s enmity with empathy to warn that not until shared sadness “fills a building” will peace live below its rafters.

[i] https://www.newstatesman.com/long-reads/2025/01/songs-dead-children-poetry-northern-ireland-s-troubles

Ceasefire

By Michael Longley

i

Put in mind of his own father and moved to tears

Achilles took him by the hand and pushed the old king

Gently away, but Priam curled up at his feet and

Wept with him until their sadness filled the building.

ii

Taking Hector’s corpse into his own hands Achilles

Made sure it was washed and, for the old king’s sake,

Laid out in uniform, ready for Priam to carry

Wrapped like a present home to Troy at daybreak.

iii

When they had eaten together, it pleased them both

To stare at each other’s beauty as lovers might,

Achilles built like a god, Priam good-looking still

And full of conversation, who earlier had sighed:

iv

‘I get down on my knees and do what must be done

And kiss Achilles’ hand, the killer of my son.’

When I read the poem, I recalled a character in Brian Friel’s great play, Translations, where one character, an Irish speaking teacher in a hedge row school, aligned Irish civilization with that of the Greeks. The teacher had no use for Shakespeare: the Irish looked past English writers to the Ancients, their true equals in bravery and achievement.

So does Michael Longley in this poem, a beautiful sonnet, which begins with Priam weeping over his son’s corpse but ending with the last Trojan king doing “what must be done.” Longley has chosen to omit the details of Hector’s death at Achilles’ hand: how Achilles had stabbed him and then dragged his body through the dust, humiliating him.

In the Iliad, Priam knows that to collect his son’s body, he will have “to embrace/The scourge and ruin of my realm and race/Suppliant my children’s murderer to implore/And kiss those hands yet reeking with their gore!” (Iliad Book XXIV). Longley closes his poem, written just a day before a ceasefire, with a father’s heroic dignity and perhaps noble resignation as he too knows the rules and costs of war.

A less mythic and therefore more intimate depiction of how the immediacy of the Conflict forced parents to explain needless violence to their children is offered in Longley’s, “The Ice Cream Man”:

Rum and raisin, vanilla, butter-scotch, walnut, peach:

You would rhyme off the flavours. That was before

They murdered the ice-cream man on the Lisburn Road

And you bought carnations to lay outside his shop.

I named for you all the wild flowers of the Burren

I had seen in one day: thyme, valerian, loosestrife,

Meadowsweet, tway blade, crowfoot, ling, angelica,

Herb robert, marjoram, cow parsley, sundew, vetch,

Mountain avens, wood sage, ragged robin, stitchwort,

Yarrow, lady’s bedstraw, bindweed, bog pimpernel.

Old men weep; children cry; nature comforts a little, memorials are patched together with the smallest of everyday objects and memories, the very innocence of an ice cream shoppe: and the violence continues.

[1] https://www.newstatesman.com/long-reads/2025/01/songs-dead-children-poetry-northern-ireland-s-troubles