Irishtown Bend Reclaimed: Restoring a Lost Cleveland Irish Neighborhood

Part 2 of the series on the legacy and future of Irishtown Bend.

To Read Part 1: https://iirish.us/2025/09/06/cleveland-irish-a-bend-in-time/

In September’s issue of iIrish, we featured Tim Callaghan’s stunning painting of Irishtown Bend, which captures both the memory of a vanished Irish neighborhood and the hope of what’s to come. That painting now serves as a visual anchor for the story unfolding on Cleveland’s West Side – a story that spans nearly two centuries and points toward a revitalized future. In this second installment, we dig deeper into the history and renewal of Irishtown

A City Built By Immigrants

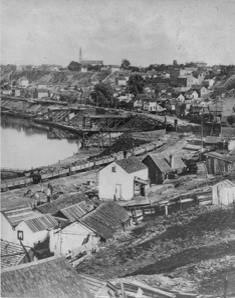

Irishtown Bend was never labeled on early Cleveland maps, but by the mid-1800s, it was widely recognized: a steep riverfront neighborhood just below Detroit Avenue and West 25th Street, hugging a tight bend in the Cuyahoga River. Emerging in the 1830s, the area became a residential enclave for Irish immigrants – many fleeing famine and seeking work. This was a working-class neighborhood where families bought small lots, raised children, tended gardens, and walked to Mass at Annunciation Church, just behind what later became the West Side Market.

Francis McGarry, writing in his column Malachi Run, reminded readers that Irishtown Bend was never just geography – it was a parish community, anchored by St. Malachi’s, where steeples rose above coal docks and saloons. He noted that by 1860, the 5th Ward, which encompassed Irishtown Bend, listed 2,499 residents in the census, including over a thousand Irish-born Clevelanders.

Families worshipped together, labored together, and leaned on both church and saloon to sustain themselves. They worked the coal docks, rail yards, and factories, hauling ore, unloading freight, and fueling the city’s growth. Neighbors were often relatives, parishioners, and co-workers bound by faith and community. Even as Hungarian, Jewish, and African American families began moving in during the early 20th century, the Irish legacy remained woven into the fabric of the neighborhood. Then came the decline.

Decline & Erasure

By the early 1900s, the Irish had largely moved onward and upward to other neighborhoods. The hillside slipped into disrepair.

The Depression brought a Hooverville shantytown, and by the 1950s, erosion and neglect left homes collapsing into the slope. City officials declared the area “blighted.”

The Cleveland Metropolitan Housing Authority seized the opportunity for urban renewal, acquiring the land and razing the remaining houses. In their place, Riverview Towers and garden apartments rose at the hilltop in the early 1960s. Fill dirt dumped along the slope destabilized the hillside, setting the stage for future landslide risks. With demolition complete, an entire community vanished, and with it, a vital piece of Cleveland’s Irish identity. Yet as McGarry often wrote, the stereotype of “shanty Irish” hardened in the public imagination only because the real story was ignored. Census data, property records, and church rosters showed that many Bend residents owned their homes, sent their children to Catholic schools, and supported parish life. He argued that what was lost in the official narrative was not simply buildings but the dignity and perseverance of immigrant families.

Archaeology and Rediscovery

In the late 1980s, archaeologists from the Cleveland Museum of Natural History excavated the hillside. They uncovered foundations, dishes, tools, toys, and medicine bottles – everyday remnants that revealed the resilience and resourcefulness of Irishtown families.

McGarry reminded the readers of these pages that these finds were not just artifacts, but fragments of full lives – children at play, mothers managing households, fathers coming home tired from the docks yet proud to provide. “Irishtown Bend,” he wrote, “was not merely a place but a people.” In 1990, the site was added to the National Register of Historic Places as the Irishtown Bend Archaeological District, cementing its importance as one of Cleveland’s earliest immigrant communities. For decades afterward, however, the hillside remained overgrown and unstable, its story untold outside of academic and local Irish circles.

Rebuilding Irishtown Bend

Momentum shifted in the 2000s when local agencies began envisioning a safer, greener future for the slope. A coalition of partners, including the Port of Cleveland, LAND studio, Cleveland Metroparks, and Ohio City Inc., launched plans to stabilize the hillside and transform it into a 25-acre public park.

Groundbreaking for the $60 million stabilization project took place in 2023. The long-term vision, known as Irishtown Bend Park, features riverfront access, bike and walking trails, gardens, an overlook promenade, and a Heritage Trail honoring immigrant communities. Sculptural outlines of vanished homes, interpretive signage, and preserved artifacts such as cisterns and carved stones will keep the past present.

Recent funding has accelerated progress: in 2024, Cleveland Metroparks secured a $10.8 million federal grant to support amphitheaters, plazas, picnic areas, a boardwalk, and completion of the Lake Link Trail. LAND studio and West Creek Conservancy also acquired more than 15 acres, clearing obsolete structures and preparing the ground for construction.

Looking Ahead at Irishtown Bend

The hillside has already been stabilized, and full construction of the park is expected to continue through 2026, with a grand opening projected in 2027 – nearly 200 years after Irish immigrants first settled along the Cuyahoga.

Soon, schoolchildren will walk the Heritage Trail, tracing the footsteps of Cleveland’s earliest Irish families. Community members will gather on green lawns and overlook the river. What was once an industrial artery for coal and ore will now be a corridor of memory, beauty, and connection.

In Francis McGarry’s writing, Irishtown Bend often emerged as both cautionary tale and symbol of endurance: a community that survived famine and prejudice only to be erased by neglect and policy yet still lived on in memory. McGarry’s words now echo in the very plans to restore the hillside. As the Heritage Trail takes shape, it will, in many ways, fulfill his vision of honoring the ordinary families who built their lives on extraordinary ground.

Cleveland is often called a city of neighborhoods. Irishtown Bend was one of its first immigrant enclaves – and for too long, one of its most forgotten. Thanks to the vision of artists, historians, and advocates, and the enduring love of community, it is being remembered, and soon, reclaimed, not just in name but in purpose.

Sources

- Margaret Lynch’s presentation on the topic at the Irish American Club East Side, June 2025

- Encyclopedia of Cleveland History – “Irishtown Bend” (Case Western Reserve University)

- Irishtown Bend (Wikipedia entry)

- History and Archaeology at Irishtown Bend: Life in a Nineteenth-Century Cleveland Irish Community (Academia.edu)

- Port of Cleveland & NOACA – Stabilization and redevelopment planning documents

- Axios Cleveland – Irishtown Bend Park will include elements to honor Cleveland’s Irish immigrants

- Cleveland Metroparks (September 2024 press release on $10.8M ORLP grant)

- West Creek Conservancy – Irishtown Bend Project Overview