By Sheila Ives

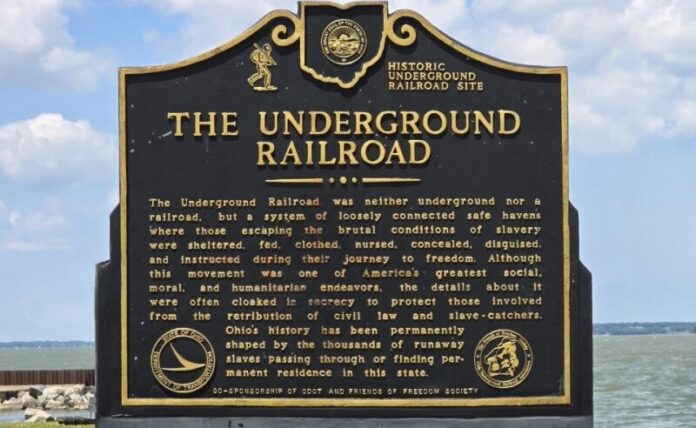

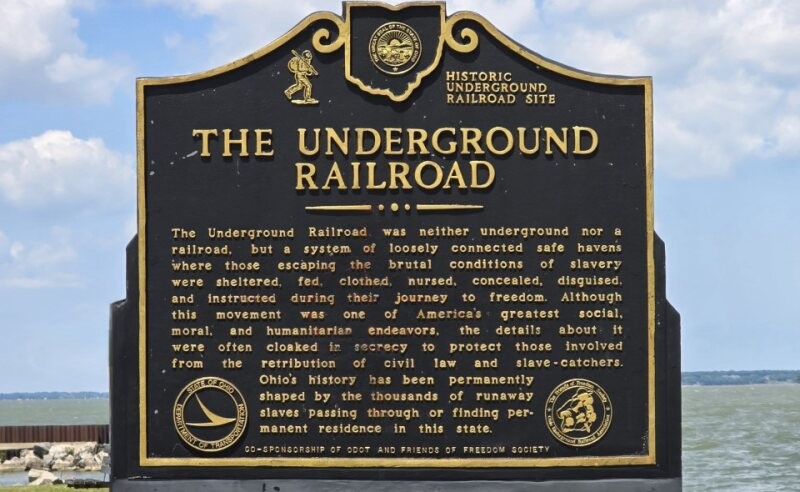

Recently a friend asked me, “Sheila, where can I find information about how fugitive slaves made their way from Ohio to Canada?” Her question piqued my interest because I grew up in Oberlin, Ohio, a town that was an important stop for the Underground Railroad, a secret network of people who helped the enslaved escape primarily during the years of 1820-1865.

I also learned about the principled abolitionists who spoke out against slavery. It is estimated that between 40,000 and 50,000 fugitive slaves came through Ohio, representing about half of the total number of slaves who escaped before the Civil War.

In 1803, the same year it entered the Union, Ohio became a free state. Although the ownership of slaves in Ohio was prohibited, its status as a free state didn’t truly provide freedom for the number of fugitive slaves who began arriving here.

The Fugitive Slave Act

State laws were passed that subjected Blacks to discrimination and legal restrictions on their rights. The Fugitive Slave Law of 1793, an act of the U.S. Congress, required Congress to enforce the Fugitive Slave Clause of the U.S. Constitution.

This law was in response to many northern states abolishing slavery, resulting in fugitive slaves seeking haven in these free states. On Sept. 18, 1850, the U.S. Congress passed the “Fugitive Slave Act.” The federal government was now expected to play a more significant role.

The act required the return of any slave to their owner without the benefit of due process, even if the slave was seized in a free state. Even freed slaves could be captured and returned to slavery.

Those who helped escaping slaves were fined $1,000.00 (equivalent to about $42, 000.00 in today’s dollars). The passage of this act heightened the dangers to the fugitive slaves and resulted in more serious consequences to those who were assisting them.

Oberlin was one of numerous stops along the Underground Railroad in Ohio. Many of the escaping slaves were making their way to places along Lake Erie, where they could find transportation to Canada and freedom.

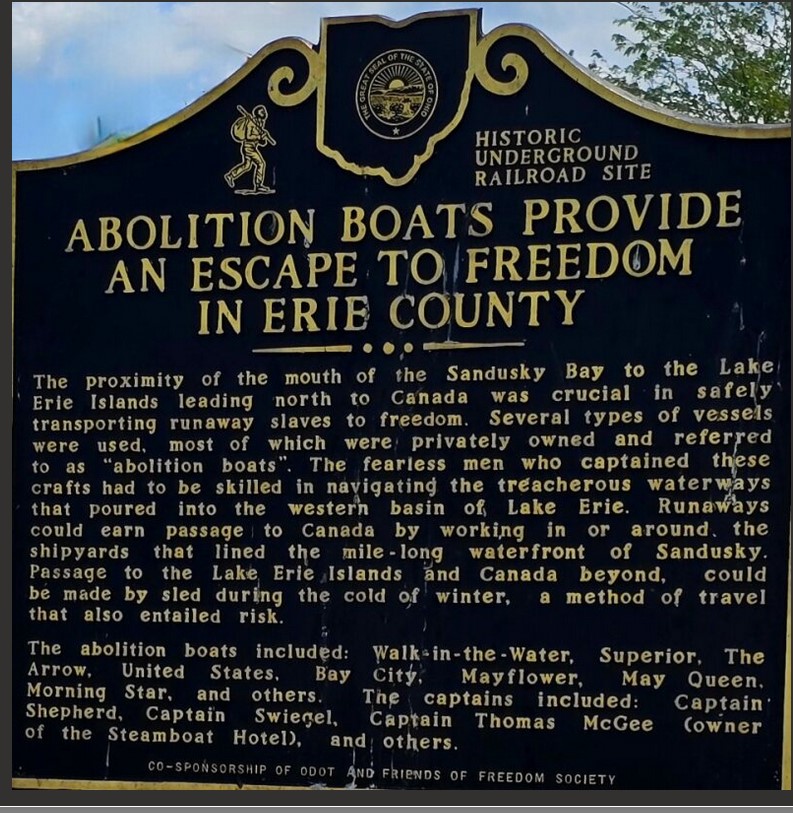

It is estimated that about 40,000 slaves made their way to Canada. One of the most significant stops in the Underground Railroad was Sandusky, Ohio, in Erie County, a town where many prominent individuals and politicians who were anti-slavery resided.

While researching the history of this town’s involvement in the Underground Railroad, I came across the name of James Nugent (1815-1887), identified as an Irish immigrant.

For many years he served as a ship captain on Lake Erie, and he was also believed to be an abolitionist who transported fugitive slaves to Canada, in what were known as “freedom ships.” Such ships also transported slaves to Canada via Lake Michigan, Lake Huron, and the Niagara River in New York.

For many years he served as a ship captain on Lake Erie, and he was also believed to be an abolitionist who transported fugitive slaves to Canada, in what were known as “freedom ships.” Such ships also transported slaves to Canada via Lake Michigan, Lake Huron, and the Niagara River in New York.

Some of the first records I found for James Nugent were the Catholic parish entries for his marriage and death. On February 5, 1844, he married Catherine Casey (1822-1887), also an Irish immigrant, in Holy Angels Catholic Church in Sandusky. They had three children; all baptized in the Catholic Church.

When James Nugent died in 1887, he was buried in St. Joseph’s Cemetery, where many Irish Catholic immigrants were interred. The priest who recorded his death entry in the parish records for Sts. Peter and Paul Catholic Church was Robert A. Sidley, an Irish immigrant priest from Co. Limerick.

Rev. Sidley was familiar to me, as he had served as executor of the estate for Rev. John Quinn, my grandmother Mary Ann Quinn’s uncle, both from Kanturk, Co. Cork. John Quinn and Robert A. Sidley were among the many Irish priests who had come to Ohio to serve the growing number of Irish immigrants who had left Ireland and settled in Ohio due to “An Gorta Mór,” The Great Hunger.

Since many Irish immigrants who came to the United States during the earlier part of the 19th century often left few records, I turned to newspaper articles hoping I might find further information about James Nugent. In the Sandusky Daily Register, dated May 6, 1884, I found an article that provided a clue about where he initially settled after leaving Ireland.

James Nugent arrived in Canada about 1835. He worked for the Hudson’s Bay Company and was stationed about 260 miles north of what is now Ottawa, at a trading post on the Gatineau River. In the article Nugent recounted a story of how he had saved the life of a young boy, a member of the Algonquin tribe, who had been riding in a canoe that overturned in the river’s rapids. In gratitude the young boy’s father gifted James Nugent with a bead-bag, a pair of moccasins, and a pipe whose bowl was made from red granite.

Another clue about when he arrived in Sandusky appeared in an article in the Sandusky Daily Register, dated November 10, 1881. There it stated that “Captain Nugent is now forty-three years a resident of Sandusky.” This indicates that he had arrived there about 1838.

James Nugent served as a captain for several schooners during the 1840s and 1850s. He spent these years transporting goods across Lake Erie, most notably to ports in New York State, such as Buffalo and Oswego.

One of the ships he commanded was named the “Home.” This 2-mast ship, about 85 feet long, was built in the summer of 1843 at the William B. Redfield shipyard in Portland (now Sandusky), Ohio. Reports of Nugent’s shipping activities could be found in local newspapers.

A notice in the Sandusky Clarion, dated June 12, 1848, announced that the schooner “Home” had arrived in the Port of Sandusky from Oswego, New York, June 8, carrying 25, 515 lbs. of mdz., 1 hhd (1 hogshead=63 U.S. gallons) of molasses, 260 bbls (barrels), and 400 bags of salt. Anti-slavery merchants would often order shipments using such cargo ships, and many of these ships were owned by abolitionists. Somewhere in the interior of such a schooner some fugitive slaves could be stowed, while others may have served as crew members.

On April 28, 1850, James Nugent took heroic action as he and his crew rescued passengers and crew aboard a sidewheel steamer named the “Anthony Wayne.” The ship had been traveling from Toledo to Buffalo, when just north of Vermilion, the ship’s two new boilers exploded. Passengers were injured by the scalding water and fire broke out on the ship.

The “Anthony Wayne” sank quickly and those surviving clung to a make-shift raft. The ship “Elmina,” captained by James Nugent, was able to rescue many of these survivors. It has been estimated that between 40 and 50 passengers and 11 crewmembers perished.

Surviving passengers wrote a card, published in the Cleveland Plain Dealer, April 30, 1850, expressing their gratitude for the aid and assistance they had received. Notably, the passengers stated, “We are grateful to Capt. Nugent, of the schooner “Elmina,” who with the character and heart of a true sailor, made all sail and every exertion in his power, to come to our rescue as soon as possible…”

More recently, James Nugent drew the attention of researchers who were gathering information for a six-part documentary entitled Enslaved: The Lost History of the Transatlantic Slave Trade, featuring actor Samuel L. Jackson, who served as host and executive producer (A book based on this series was co-authored by Simcha Jacobovici and Sean Kingsley). These researchers were looking into how slaves were transported to Canada, and they were intrigued that for a few months in 1848 the whereabouts of the schooner “Home” couldn’t be determined. No paperwork or documentation for its location or cargo could be found to account for this gap.

The researchers wondered if James Nugent had been transporting slaves during those missing months. At the Firelands Historical Society in Norwalk, Ohio, they found archival evidence that persuaded them that he could have been ferrying fugitive slaves to Canada that year based on the following, well-publicized incident.

On October 20, 1852, Rush R. Sloane, a prominent Sandusky attorney and abolitionist, interceded to help seven runaway slaves who had been captured and brought to the mayor’s office. Sloane asked for documentation from the slave catchers to prove that these were indeed escaped slaves.

When the slave catchers couldn’t provide the necessary documentation, Sloane told the slaves there was no reason for them to be held, and members of the crowd that had gathered quickly guided the slaves out of the building. Later, these fugitive slaves boarded a waiting ship that transported them to Canada. Attorney Sloane was fined over $3,000.00 for assisting the slaves to escape.

The researchers still needed further proof that James Nugent was the ship captain in question. They read a letter from the mayor of Clyde, Ohio, a town about 19 miles southwest of Sandusky, who had witnessed Sloane releasing the slaves.

In the letter, he stated, “That party of fugitive slaves was carried to Canada concealed in the hold of the sailing vessel by a lake captain, then and now a robust Democrat in politics, a man with a conscience and a heart, resident of one of the lake cities.” He continued, however, “My lips are sealed for the lifetime of my informant.”

Fortunately, further digging resulted in the discovery of these words stated by attorney Rush R. Sloane about the incident: “These fugitives were the same night received on a small boat by Captain James Nugent, a noble man now dead, then living at Sandusky and secreted on board the vessel; he commanded these seven and on the second day after were safely landed in Canada.”

He further revealed that these seven slaves were members of two families. This was the proof these researchers needed to verify that James Nugent was an abolitionist and also the captain who had saved these slaves and likely many others in his trips to New York.

Harriet Tubman

One question remained, however. How exactly did James Nugent accomplish the delivery of these slaves to Canada? John Polacsek, a Great Lakes historian, was able to provide the answer they were seeking. In the shipping notice mentioned earlier, indicating that James Nugent arrived in the Port of Sandusky on June 8, 1848, the key piece of information was that he was returning from Oswego, New York. In order for the ship “Home” to reach Oswego, it had to go through the Welland Canal, located in the Niagara peninsula of Ontario, Canada. This canal is the artery that connects Lake Ontario and Lake Erie.

As the boat was being lowered into the canal, slaves were able to jump onto land and head for St. Catherines, Ontario, a place known for its abolitionist activities and a major settlement for former slaves. The noted abolitionist and conductor Harriet Tubman lived in St. Catherines from about 1852 to 1857 assisting former slaves adjust to their new lives there.

At some point during the 1850s, James Nugent left the shipping life. In the 1860 census for Sandusky, he is listed as working as a railroad agent. According to newspaper accounts, he was employed by the Lakeshore Railroad Company.

The 1860 census also indicated that he and his wife Catherine had three children, whose ages then ranged from four to nine years old. He worked for the railroad for several years and continued to be involved in civic affairs and politics, at one time serving as president of the Sandusky Water Board.

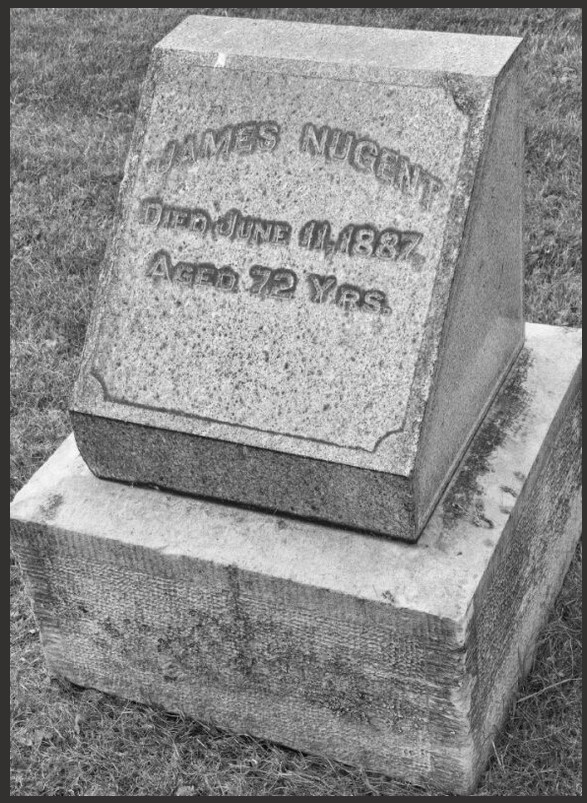

Even though his days as a ship commander were many years behind him, he continued to be called “captain.” His death notice appeared in the Sandusky Daily Register, dated June 13, 1887: “In this city on June 11th, 1887, at 4 a.m., Capt. James Nugent, in his 72nd year. Funeral from Sts. Peter and Paul’s church this morning at 9 o’clock. Friends of the family are invited.”

In mid-June I visited the city of Sandusky. My first stop was St. Joseph’s Cemetery to see the monument for Rev. John Quinn, my grandmother’s uncle. Next, with the assistance of a map, I located the grave site for James Nugent.

His headstone was simple and modest, providing only his name, date of death, and his age. His wife and one of his three children are also buried near him. As I walked through the neat cemetery rows, I noted the names of so many Irish immigrants who had come to Sandusky. They too had boarded a ship to take them to another country for the chance of a better life.

Before I left the city, I went to the shoreline of Lake Erie, the critical launching site for so many escapes. At the Jackson Street Pier, large cumulus clouds floated above the choppy water as the flags of Ohio, the United States, and Canada billowed in the wind. I thought of all the determined fugitive slaves who had made the dangerous, arduous journey to Ohio.

As I gazed across the water, I reflected on the courage of the noble, decent James Nugent and others like him who had risked their lives to help these slaves gain their freedom. An Irish seanfhocal (proverb), slightly changed here, came to my mind: ”Bíonn súil leis an loch”—There is hope with the lake.

Many faced possibly more perils–even death–as they boarded a small schooner that took them across the potentially treacherous Lake Erie to Canada. In fact, the schooner Home was involved in a collision with another ship on Lake Michigan in 1858. The Home now rests in the cold depths of this lake near Cleveland, Wisconsin.

Images: https://www.wisconsinshipwrecks.org/Vessel/Details/277?region=Index).