By Dr. Jeanne Colleran

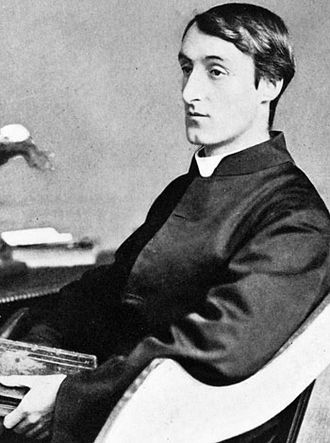

The next time I am in Dublin, I will go to Glasnevin Cemetery, to the Jesuit plot, and leave a small oval-shaped blue-hued stone at the foot of the cross where Gerard Manley Hopkins’ name is engraved. The great nineteenth-century poet is buried there, far from his London birthplace, but in the city where he spent the final years of his brief life.

His actual grave is unmarked, though the Irish Jesuits recently set about restoring the weathered plots. You can see the plot where Hopkins was buried in 1889, age 45, in this short video posted y the Irish Jesuits: https://vimeo.com/335383897.

I hope the stone will be mistaken for a thrush’s egg. Hopkins spent the last five years of his life as a professor of Greek and Latin at University College Dublin, living in Newman House on Stephen’s Green. The general consensus is that he was very unhappy. He died from typhoid fever.

We Irish may feel a flicker of accusation about his misery. Perhaps the truth is the Irish forbearance for melancholy reflection was too hospitable an environment for G.M.

The Oxford Movement got its hooks into Hopkins while he was a (brilliant) student at the University, and then Cardinal Newman and the Jesuits leveled the final coup de foudre (sort-of) by drawing him into the order. Leaving his family’s Anglican faith and converting to Roman Catholicism caused a permanent rift.

He also thought his writing was at odds with his religious duties, so he burned some of his early poems and refused to have the rest published during his lifetime. At UCD, he was an Englishman living in Ireland during the stirrings of nationalism and revolution.

He composed his famous “terrible sonnets” (with terrible meaning terrifying) during this period, and they reveal not only his deep loneliness, but also his intense scrupulousness, exacerbated by a feeling of divine abandonment. Hopkins neared despair, but against expectation, his last words were, “I am so happy.”

Yet, Hopkins’ poems also tell us that with persistent attentiveness, we can gain a luminous awareness of how natural beauty reveals divine immanence. We need to see everything as being, as he says in another poem, “charged with the grandeur of God.”

To invoke how the divine animates creation, Hopkins developed a poetic style consisting of “sprung” rhythm (a pattern of placing stressed syllables close to each other) and the melding of noun and verb to obscure the difference between “being” and “acting.” In the poem below, words like “thrush” and “shoots” are examples. Hopkins’ poetic method was deeply Catholic and recognizably Jesuit: grasping the divine in creation was a form of divine consolation, the interior movement in the soul, according to Saint Ignatius, when it feels the love of the Creator.

Here is the first stanza of the sonnet “Spring,” written when Hopkins lived in another Celtic country, Wales. It demonstrates a few of Hopkins’ poetic/metaphysical practices, but first I suggest you read it aloud. It is so lovely; you might commit it to memory to welcome spring—however late it arrives in Ohio and Pennsylvania.

Nothing is so beautiful as Spring-

When weeds in wheels shoot long and lovely and lush,

Thrush’s eggs look little low heavens, and thrush

Through the echoing timber does so rinse and wring

The ear, it strikes like lightenings to hear him sing;

The glass peartree leaves and blooms, they brush

The descending blue; that blue is all in a rush

With richness, the racing lambs too have fair their fling.

In a diary entry, Hopkins wrote, “I do not think I have ever seen anything more beautiful than the bluebell I have been looking at. I know the beauty of the Lord by it. Its strength and grace.”

In “Spring,’ Hopkins does not want merely to say something about nature’s beauty, as he does in his diary entry; he wishes to recreate the experience of seeing Spring quicken into abundance, revealing God. Hopkins looks at the unfurled leaves (the “wheels”) which will shoot into beauty. He chooses virtually every word for its double description of nature and nature’s movement. The speaker re-appears in the second stanza asking:

What is all this juice and all this joy?

A strain of the earth’s sweet being in the beginning

In Eden garden. Have, get, before it cloy,

Before it cloud, Christ, lord, and sour with sinning,

Innocent mind and Mayday in girl and boy,

Most, O maid’s child, thy choice and worthy the winning.

His answer to the question is to beg Christ to preserve the purity in nature and in humans – “the Mayday in girl and boy.” The final phrase affirms the inherent value of creation, including humans, because we are “worthy the winning I wanted to share this poem because it captures the dynamism of spring and the uplift of faith. It is one of Hopkins’ most beautiful and theologically rich, along with “Pied Beauty,” “God’s Grandeur,” and “The Windhover.”

I used the poem in a teaching demonstration when I was being considered for tenure at John Carroll. The Jesuit professor (now deceased) who observed seemed to approve my choice and my explanation, though he also recommended I work on my posture. Every Jesuit-educated person will understand why I’ve added this story.

We ought to know the works of this English Jesuit who spent extended periods among the Celts since Catholicism, melancholia, poetry, and spirituality are in our history and psyches. We might also consider that we in Cleveland (and Cincinnati) live in a Jesuit city, one of twenty-seven in the United States.

This is not to say that that the Jesuits have made more of a contribution than any other religious or civic organization (though they may think so!), but it is a mark of some distinction. Having numerous Jesuit secondary schools, parishes, and universities in Ohio means we are fortunate to have men and women formed in service to each other, and especially, in service to the vulnerable.

It also means that many have been schooled in a particular kind of critical thinking, one that joins contemplation to the imagination in colloquial familiarity with a God who guarantees both freedom and love. That’s the best way to read Hopkins.

Find this and other Dr, Colleran Irish Lit Columns HERE!

*Dr. Jeanne Colleran, Ph.D is Professor Emeritus of English. At John Carroll University she served as Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences and as the Provost and Academic Vice President. At Loyola University of Chicago, she worked with the Loyola Rule of Law Institute in the School of Law.

A scholar of modern and contemporary literature, she has published a book, an edited collection, and some three dozen articles concerning literature and society. She has lectured in Ireland, South Africa, England, United States, France, Canada, Belgium, and The Netherlands. She taught undergraduate and graduate courses in Irish Literature. She may be reached at [email protected]

ends

Monthly newsmagazine serving people of Irish descent from Cleveland to Clearwater. We cover the movers, shakers & music makers each and every month.

Since our 2006 inception, iIrish has donated more than $376,000 to local and national charities.

GET UPDATES ON THE SERIOUS & THE SHENANIGANS!