By Mike Finn

“Charge and spare no rebel!”

The 1798 United Irish Rebellion was an insurrection launched by the United Irishmen, an underground republican society, composed of both Presbyterians (known as Dissenters) and Catholics aimed at severing the connection with England and establishing an Irish Republic based on the principles of the French Revolution.

The English have rarely been restrained in their efforts at suppressing Irish rebellions, and the actions of the crown forces during 1798 were a prime example. Public executions without trial of men, women, and Catholic religious were common for anyone suspected of participating in the rebellion or helping the rebels.

The United Irish rebellion was strongly supported in the County Kildare area, and it was on the Curragh of Kildare that the worst atrocities and suppression of the rising were witnessed. According to historian R. F. Foster, the 1798 rebellion was “probably the most concentrated episode of violence in Irish history.”

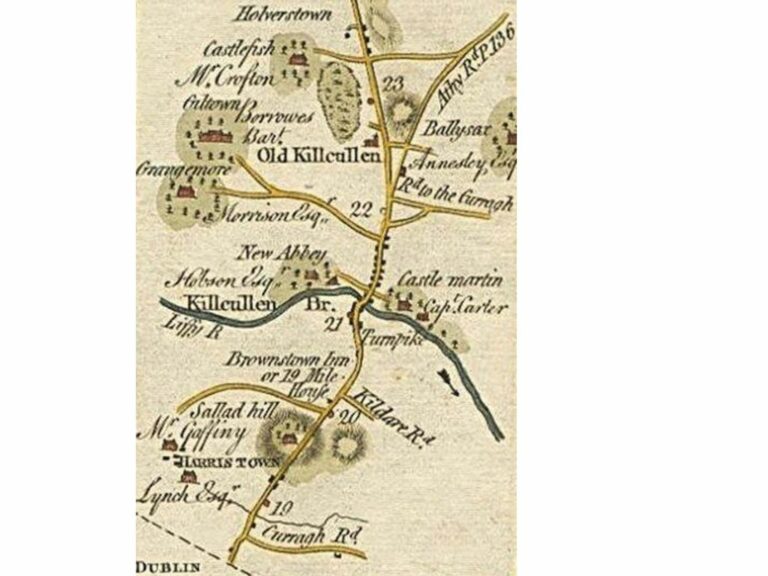

One of the more despicable actions during the 1798 Rebellion occurred in a place known as Gibbet Rath in the Curragh, which is about three miles southeast of the town of Kildare (A gibbet is an English word meaning an upright post with a projecting arm for hanging the bodies of executed criminals. A rath is an Irish word meaning an ancient circular enclosure or fort surrounded by an earthen wall).

The rebellion began in County Kildare as the rebels took over several towns in the Kildare area, where over 1,000 rebels held the government forces at bay for over a week. Eventually, the rebels were forced to surrender and sought terms from the British.

News of the outbreak of the rebellion in Kildare prompted General Sir James Duff, a ruthless British military commander in Limerick, to gather a force of about 600 men, mainly Dublin militia members, and set out on a march to Dublin on May 27, 1798. His twin objectives were to restore communications between Kildare and Dublin and to crush any rebel resistance encountered on the way.

Meanwhile in Kildare, following the rebel defeat at the Battle of Kilcullen, the rebels had been forced to surrender at Knockaulin Hill on May 27. The terms offered by British General Sir Ralph Dundas, Commander of the Midland District Militia, were that the rebel force would cease hostilities, retreat to Gibbet Rath, and stack their weapons in return for a government amnesty.

The amnesty agreement would allow the surrendering rebels to return to their homes unharmed. The rebels accepted the offered terms and agreed to turn over their weapons at Gibbet Rath on the Curragh.

Arriving in County Kildare, General Duff was unaware that the rebels were gathering to surrender on the Curragh plain. He reinforced his column and marched to the nearby town of Kildare. According to reports from Kildare town, several from Duff’s Foxhunter Division, in a riotous and drunken state, marched through the streets with fixed bayonets swearing loudly, “we are the boys who will slaughter the croppies tomorrow at the Curragh” (croppies was a derogatory name for Catholics).

General Duff’s force had by now grown to 700 militia, dragoons and yeomanry. The designated place of surrender, the ancient fort of Gibbet Rath, was a wide expanse of plain with little or no cover for several miles around, but neither the rebels nor Duff’s force had seemingly any reason to fear treachery, as a peaceful surrender had been accomplished without bloodshed.

By the time of Duff’s arrival at Gibbet Rath on the morning of May 29, 1798, an army of roughly 2,000 rebels were waiting to surrender in return for the promised amnesty. Even though they had complied with the terms of the surrender by stacking their arms, they were subjected to an angry tirade for their treason by General Duff, who ordered his army to surround the rebels.

What happened next is still debated. General Duff claims that the rebels fired on his troops. This is unlikely as they were surrendering and turning in their weapons. Duff was overheard ordering his troops to “charge and spare no rebel.”

The resulting infantry and cavalry assault resulted in the death of about 350 unarmed rebels (some accounts say it was over 500). Hundreds were also wounded and many fled in panic.

General Duff redrafted his own official report of the engagement before submission to Dublin Castle. His final draft was transmitted without the references to his knowledge of the surrender preparations. It read: “We followed them (the rebels) with Dragoons. Unfortunately, some of them fired on the Troops; from that moment they were attacked on all sides, nothing could stop the rage of the troops.”

One of Duff’s commanders wrote he left “500 rebels bleaching on the Curragh of Kildare” and that the “Curragh was strewed with the vile carcasses of popish rebels …”

Far from being censured for the massacre, General Duff upon his arrival in Dublin was celebrated as a hero by the British establishment, who honored him with a victory parade. General Dundas, by contrast, was denounced for having shown clemency towards the rebels. However, as news of the massacre spread, rebels were discouraged from surrendering to British troops or militia.

Some of the rebels were buried in Kildangan and their names are recorded there. Others were buried in the Grey Abby in Kildare and

some in Nurney.

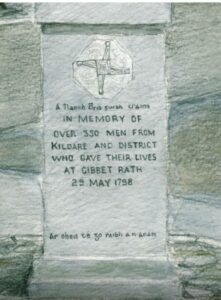

The statue of Saint Brigid at the Market Square of Kildare (pictured) is dedicated to the memory of the victims at Gibbet Rath. The inscription reads: “In memory of over 350 men from Kildare and district who gave their lives at Gibbet Rath, May 1798.” The statue was erected at the Market Square in 1976.

Find this column and others from the September 2023 issue here!

*J. Michael Finn is the Ohio State Historian for the Ancient Order of Hibernians and Division Historian for the Patrick Pearse Division in Columbus, Ohio. He is also past Chairman and Life Member of the Catholic Record Society for the Diocese of Columbus, Ohio. He writes on Irish and Irish-American history; Ohio history and Ohio Catholic history. You may contact him at [email protected]

Monthly newsmagazine serving people of Irish descent from Cleveland to Clearwater. We cover the movers, shakers & music makers each and every month.

Since our 2006 inception, iIrish has donated more than $376,000 to local and national charities.

GET UPDATES ON THE SERIOUS & THE SHENANIGANS!