Walk East Until I Die

by Mike Pinnock

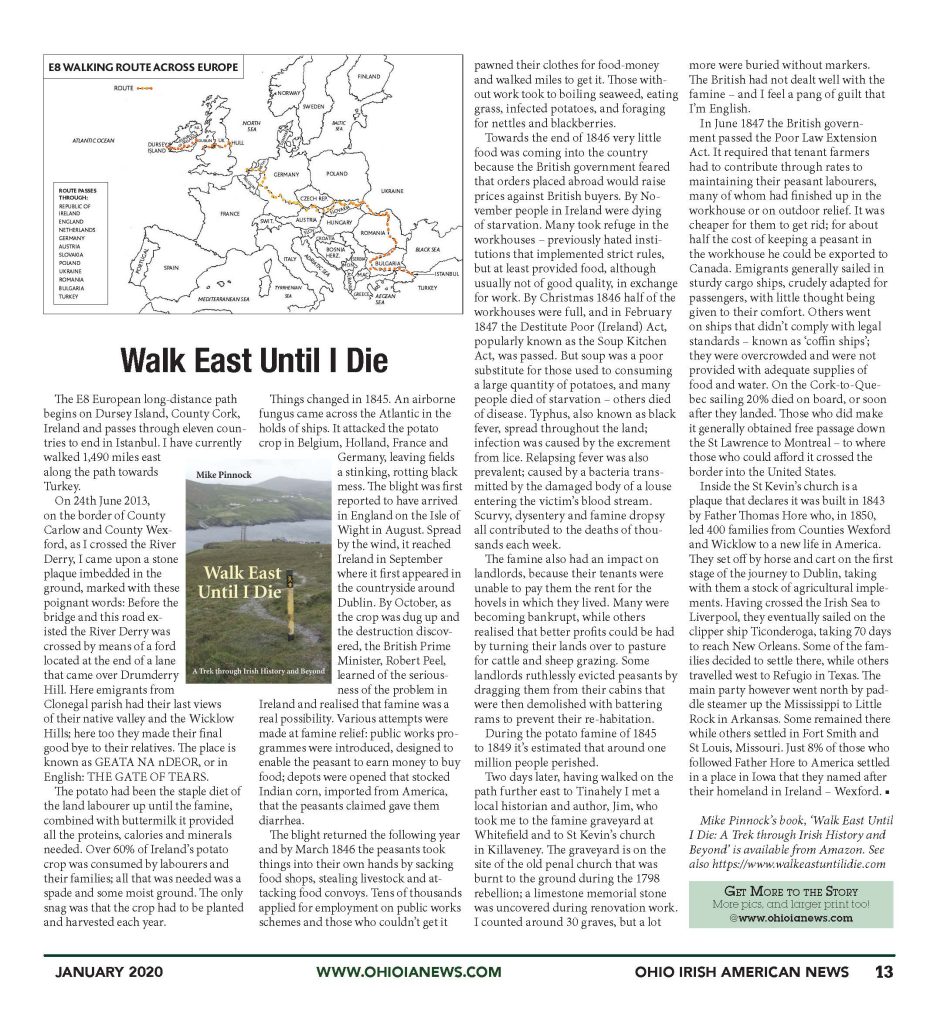

The E8 European long-distance path begins on Dursey Island, County Cork, Ireland and passes through eleven countries to end in Istanbul. I have currently walked 1,490 miles east along the path towards Turkey.

On 24th June 2013, on the border of County Carlow and County Wexford, as I crossed the River Derry, I came upon a stone plaque imbedded in the ground, marked with these poignant words: Before the bridge and this road existed the River Derry was crossed by means of a ford located at the end of a lane that came over Drumderry Hill. Here emigrants from Clonegal parish had their last views of their native valley and the Wicklow Hills; here too they made their final good bye to their relatives. The place is known as GEATA NA nDEOR, or in English: THE GATE OF TEARS.

imbedded in the ground, marked with these poignant words: Before the bridge and this road existed the River Derry was crossed by means of a ford located at the end of a lane that came over Drumderry Hill. Here emigrants from Clonegal parish had their last views of their native valley and the Wicklow Hills; here too they made their final good bye to their relatives. The place is known as GEATA NA nDEOR, or in English: THE GATE OF TEARS.

The potato had been the staple diet of the land labourer up until the famine, combined with buttermilk it provided all the proteins, calories and minerals needed. Over 60% of Ireland’s potato crop was consumed by labourers and their families; all that was needed was a spade and some moist ground. The only snag was that the crop had to be planted and harvested each year.

Things changed in 1845. An airborne fungus came across the Atlantic in the holds of ships. It attacked the potato crop in Belgium, Holland, France and Germany, leaving fields a stinking, rotting black mess. The blight was first reported to have arrived in England on the Isle of Wight in August. Spread by the wind, it reached Ireland in September where it first appeared in the countryside around Dublin. By October, as the crop was dug up and the destruction discovered, the British Prime Minister, Robert Peel, learned of the seriousness of the problem in Ireland and realised that famine was a real possibility.

Various attempts were made at famine relief: public works programmes were introduced, designed to enable the peasant to earn money to buy food; depots were opened that stocked Indian corn, imported from America, that the peasants claimed gave them diarrhoea. The blight returned the following year and by March 1846 the peasants took things into their own hands by sacking food shops, stealing livestock and attacking food convoys. Tens of thousands applied for employment on public works schemes and those who couldn’t get it pawned their clothes for food-money and walked miles to get it. Those without work took to boiling seaweed, eating grass, infected potatoes, and foraging for nettles and blackberries.

Towards the end of 1846 very little food was coming into the country because the British government feared that orders placed abroad would raise prices against British buyers. By November people in Ireland were dying of starvation. Many took refuge in the workhouses – previously hated institutions that implemented strict rules, but at least provided food, although usually not of good quality, in exchange for work.

By Christmas 1846 half of the workhouses were full, and in February 1847 the Destitute Poor (Ireland) Act, popularly known as the Soup Kitchen Act, was passed. But soup was a poor substitute for those used to consuming a large quantity of potatoes, and many people died of starvation – others died of disease. Typhus, also known as black fever, spread throughout the land; infection was caused by the excrement from lice. Relapsing fever was also prevalent; caused by a bacteria transmitted by the damaged body of a louse entering the victim’s blood stream. Scurvy, dysentery and famine dropsy all contributed to the deaths of thousands each week.

The famine also had an impact on landlords, because their tenants were unable to pay them the rent for the hovels in which they lived. Many were becoming bankrupt, while others realised that better profits could be had by turning their lands over to pasture for cattle and sheep grazing. Some landlords ruthlessly evicted peasants by dragging them from their cabins that were then demolished with battering rams to prevent their re-habitation.

During the potato famine of 1845 to 1849 it’s estimated that around one million people perished.

Two days later, having walked on the path further east to Tinahely I met a local historian and author, Jim, who took me to the famine graveyard at Whitefield and to St Kevin’s church in Killaveney. The graveyard is on the site of the old penal church that was burnt to the ground during the 1798 rebellion; a limestone memorial stone was uncovered during renovation work. I counted around 30 graves, but a lot more were buried without markers. The British had not dealt well with the famine – and I feel a pang of guilt that I’m English.

In June 1847 the British government passed the Poor Law Extension Act. It required that tenant farmers had to contribute through rates to maintaining their peasant labourers, many of whom had finished up in the workhouse or on outdoor relief. It was cheaper for them to get rid; for about half the cost of keeping a peasant in the workhouse he could be exported to Canada.

Emigrants generally sailed in sturdy cargo ships, crudely adapted for passengers, with little thought being given to their comfort. Others went on ships that didn’t comply with legal standards – known as ‘coffin ships’; they were overcrowded and were not provided with adequate supplies of food and water. On the Cork-to-Quebec sailing 20% died on board, or soon after they landed. Those who did make it generally obtained free passage down the St Lawrence to Montreal – to where those who could afford it crossed the border into the United States.

Inside the St Kevin’s church is a plaque that declares it was built in 1843 by Father Thomas Hore who, in 1850, led 400 families from Counties Wexford and Wicklow to a new life in America. They set off by horse and cart on the first stage of the journey to Dublin, taking with them a stock of agricultural implements. Having crossed the Irish Sea to Liverpool, they eventually sailed on the clipper ship Ticonderoga, taking 70 days to reach New Orleans.

Some of the families decided to settle there, while others travelled west to Refugio in Texas. The main party however went north by paddle steamer up the Mississippi to Little Rock in Arkansas. Some remained there while others settled in Fort Smith and St Louis, Missouri. Just 8% of those who followed Father Hore to America settled in a place in Iowa that they named after their homeland in Ireland – Wexford.

Mike Pinnock’s book, ‘Walk East Until I Die: A Trek through Irish History and Beyond’ is available from Amazon. See also https://www.walkeastuntilidie.com

Monthly newsmagazine serving people of Irish descent from Cleveland to Clearwater. We cover the movers, shakers & music makers each and every month.

Since our 2006 inception, iIrish has donated more than $376,000 to local and national charities.

GET UPDATES ON THE SERIOUS & THE SHENANIGANS!