Illuminations: Who Was St. Patrick’s Uncle?

By: J. Michael Finn

“Wherever Christ is known, Martin is honored.”

– Latin poet, St. Venantius Fortunatus

What do we know about the relatives of St. Patrick?

There are many writings about St. Patrick and it is often difficult to determine if you are reading historical fact or legend. In order to learn more about Patrick’s relatives we have to follow some breadcrumbs left by Patrick himself, as well as, a few of his ancient biographers.

The Confessions of St. Patrick is generally accepted to have been written by St. Patrick himself, just before his death about 461 AD. In it, Patrick tells us about his father and grandfather: “My father was Calpurnius. He was a deacon (a senator and tax collector); his father was Potitus, a priest who lived at Bannavem Taburniae.” No other relatives are mentioned by Patrick.

The later writings on the life of Patrick do not appear until over a century after his death, when Patrick became famous. Some of these ancient writings often claim to be based on previous writings that have been lost or destroyed.

Bishop Tírechán (pron: teer-a-hahn) is known to have authored one work, known as the Collectanea (written in Latin between 688 and 693). This is a biography of St. Patrick and has been preserved in the Book of Armagh, which dates from the second half of the seventh century. Tírechán says that he drew on the oral and lost written testimony of Bishop Ultán, who was his teacher. According to Tírechán, Patrick’s mother name was Concessa.

Muirchú (pron: mur-a-hoo) was a monk and historian born in Leinster, sometime in the seventh century. About 700, he wrote the Vita Sancti Patricii, known in English as The Life of Saint Patrick. The Latin version that survived in Ireland was also included within The Book of Armagh. Muirchú records much the same information as Tírechán, reporting that “Moreover his (Patrick’s) mother’s name was Concessa.”

In the Life of St Patrick, written by the English Cistercian monk Jocelin of Furness (about 1180), Patrick is represented as the nephew of St Martin of Tours, the Patron Saint of France. Jocelin was the first to claim that the Patrick and Martin were related. Jocelin wrote, “Concessa was his mother’s name. She was of the Franks, and a sister to Martin.”

The phrase “of the Franks” means that she was a member of a Germanic-speaking people who invaded the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century. Dominating present-day northern France, Belgium, and western Germany, the Franks established the most powerful Christian kingdom of early medieval Western Europe.

Who was St. Martin of Tours?

Martin was born in 316 AD in Savaria in the Diocese of Pannonia (now part of, Hungary). His father was an officer in the Roman army. A few years after Martin’s birth, his father was allocated land on which to retire at Ticinum, in northern Italy, where Martin grew up. At age ten, Martin began studying Christianity, as it had been declared legal in the Roman Empire.

As the son of a veteran officer, Martin at fifteen was required to join the Roman cavalry that was part of the bodyguard of the emperor. At the age of eighteen (around 334 or 354), he was stationed in Gaul near the city of what is now Amiens, France.

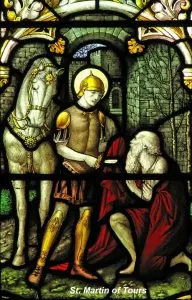

While at Amiens, Martin had an experience, which became the most-repeated story about his life. One day as he was approaching the gates of the city of Amiens, he met a scantily clad beggar. It was a cold day and Martin felt sorry for the poor man.

Martin had no money or provisions to share with the beggar. So, Martin removed his red military cloak, divided it in two with his sword and gave half of the cloak to the beggar, keeping the other half for himself.

That night, Martin had a vision of Jesus in Heaven surrounded by a group of angels. To his surprise, Jesus was wearing half of a Roman soldier’s cloak. One of the angels asked Jesus, “Master, where did you get that old dirty and torn cloak?” Jesus replied, “My good servant Martin gave it to me.”

The vision confirmed Martin in his piety and he was baptized at the age of eighteen. It also encouraged Martin to request release from military service. He told his military commanders, “I am the soldier of Christ; it is not lawful for me to fight.”

Soon after leaving the Roman military, Martin became a monk. His holiness became so popular that the people of Tours insisted he serve as their bishop. Reluctantly, he then became Bishop of the Diocese of Tours, in what is now France.

Chaplains and Chapels

After his death in 397, it is reported that Martin’s half of his old Roman military cloak was preserved as a relic and was often carried into battle by Frankish kings. The kings entrusted the cloak to a priest who was called a cappellanu, or “keeper of the cape.” Eventually, all priests who served the military were called cappellani.

The French translation is chapelains, from which the English word chaplain is derived. A similar development took place for the term referring to small temporary churches built to hold the relic. People called them a capella, the word meaning “little cloak.” Eventually, all small churches began to be referred to as chapels.

Did Patrick ever meet St. Martin? Following his escape from slavery in Ireland, Patrick was set on devoting himself to the service of God in the sacred ministry. His biographers report that Patrick first traveled to Marmoutier Abbey at Tours, France (founded by St. Martin in 372). There he studied under Martin, who reportedly gave Patrick the monk’s habit and tonsure (religious haircut). Patrick was present at Marmoutier Abbey in 397 when Martin died.

Later Patrick visited the island monastery of Lérins Abbey, a Cistercian monastery, in France, which was well known for learning and piety. Patrick completed his theological studies at the Benedictine monastery of Auxerre Abbey in central France. Its founder, St. Germanus, is said to have ordained Patrick to the priesthood. Patrick returned to Ireland as a missionary and as bishop, where he converted Ireland to Christianity.

Likely due to the connection with Patrick, St. Martin’s Day, or Martinmas, on November 11 has been celebrated in Ireland for thousands of years. People never turned a wheel on St Martin’s Day be it a mill wheel, plough wheel or a spinning wheel. It was also believed to be very unlucky for fishermen to fish on that day.

Martinmas was often referred to as the “Old Halloween.” Many churches across Ireland also carry the name of St. Martin of Tours.The Latin poet, St. Venantius Fortunatus, famously declared, “Wherever Christ is known, Martin is honored,” which might also be true of St. Martin’s nephew, St. Patrick.

*J. Michael Finn is the Ohio State Historian for the Ancient Order of Hibernians and Division Historian for the Patrick Pearse Division in Columbus, Ohio. He is also Chairman of the Catholic Record Society for the Diocese of Columbus, Ohio. He writes on Irish and Irish-American history; Ohio history and Ohio Catholic history. You may contact him at [email protected].