By Moyra Michelle Nguyen

The best thing about being Irish in America is the level of love that I feel from and towards my Irish community. I remember my first ever trip to America was spending a summer in New York in my early 20s. It was like a home from home, being welcomed without question by the Irish American community everywhere I went.

I always thought that that was normal, until amongst a group of international colleagues while living in London, they shook their heads in puzzlement at my belief. No, that’s not how other countries do it, they felt, not understanding any concept of feeling any responsibility towards their countrymen.

They asked, “What is that about anyway?” Now being on British soil at the time, I bit my tongue, but I can say it here. When you take away everything from other people, their land, their livelihoods, their food, their natural resources, their language, their schools, their churches, their customs, their religion, their reputations, and their dignity, what else do they have to cling to, but each other?

That brings me to the heaviest thing we experience in being Irish; the struggle that we carry in our blood and our bones from the violent oppression our ancestors endured over 800 years of British colonization of our homeland. We were a land of emerald riches; saints and scholars; magic and luck; of community with nature and God. We had wild warrior queens and mythical giants.

As Celts we were fierce, yet we coexisted with the softness of the faeries. I’m not sure when we became ‘the land of 100,000 welcomes,’ but we had some very unwelcome visitors for a long time.

How can we comprehend 800 years of the struggle? 800 years. What capacity do we even have within us to consider the enormity of the suffering and for our neighbors in Northern Ireland still their lived experience? For the rest of us, it lives on in our habits or ways of thinking and being, that we find normal.

Numbing the Pain

Maybe it’s always needing the cupboards to be filled full of food lest you might go hungry. Perhaps it’s needing to finish everything on your plate because food still feels scarce. More commonly it is the drinking and other addictions to help us numb the pain that we feel, and don’t even know why it’s there.

Revisiting history is not easy; it can seem like opening old wounds. My mother doesn’t even like the word ‘Protestant’ being used because of the division it has sown.

The first 400 years of colonization or settlements that were an intermingling of peoples; it happened for 1000s of years before that, and most settlers assimilated into Irish culture. It was from the 1400s onwards that the violent strategies of taking full possession of the land and domination of her people took hold.

If I were to put myself in the shoes of my ancestors, I think for the first 100 years I’d be angry and ready to fight. The second 100 years I’d be even more angry and fight like hell.

Then the third 100 years, wow. I think I started to feel somewhat defeated and even hopeless. Then in the fourth century, I’d be ready for that famine to come and take me out.

So many generations and yet somehow, our ancestors did keep going. The population of Ireland halved at that time. Halved. The Sligo poet W.B. Yeats describes the despair and hopelessness in his poem,

‘The Ballad of Father Gilligan,’

‘The old priest Peter Gilligan

was weary night and day.

For half his flock were in their beds

or under green sods lay.

I have no rest, nor joy, nor peace.

For people die and die

And after cried he ‘God forgive!’

My body spake not I’

How far we have come in the past 100 years since achieving the Irish Free State, building the Irish Republic, and restoring the dignity of Eireann? Having decolonized our lands, it’s now time to decolonize our hearts and minds.

It’s time for healing. It’s time to thaw out all the numbness, all the unspoken pain and unsaid traumas that have been allowed to turn into stony silence and addiction. This will truly be the hardest thing any of us Irish people will do in our lifetimes.

Not just because of the sheer immensity of the pain, but it’s compounded by successive generations of parents, priests, teachers, and leaders, who went through it with us.

Intergenerational Trauma

This is what intergenerational trauma is. It’s like PTSD that is inherited without us even being aware. Pulling this pain from the past into the present day requires great emotional courage. And just in case we doubted we were ready, God brought it before us to witness in real time, so that we couldn’t continue to look away. We can’t go back and save our ancestors, but perhaps we can stop it from happening to anyone else ever again … and find healing in this way.

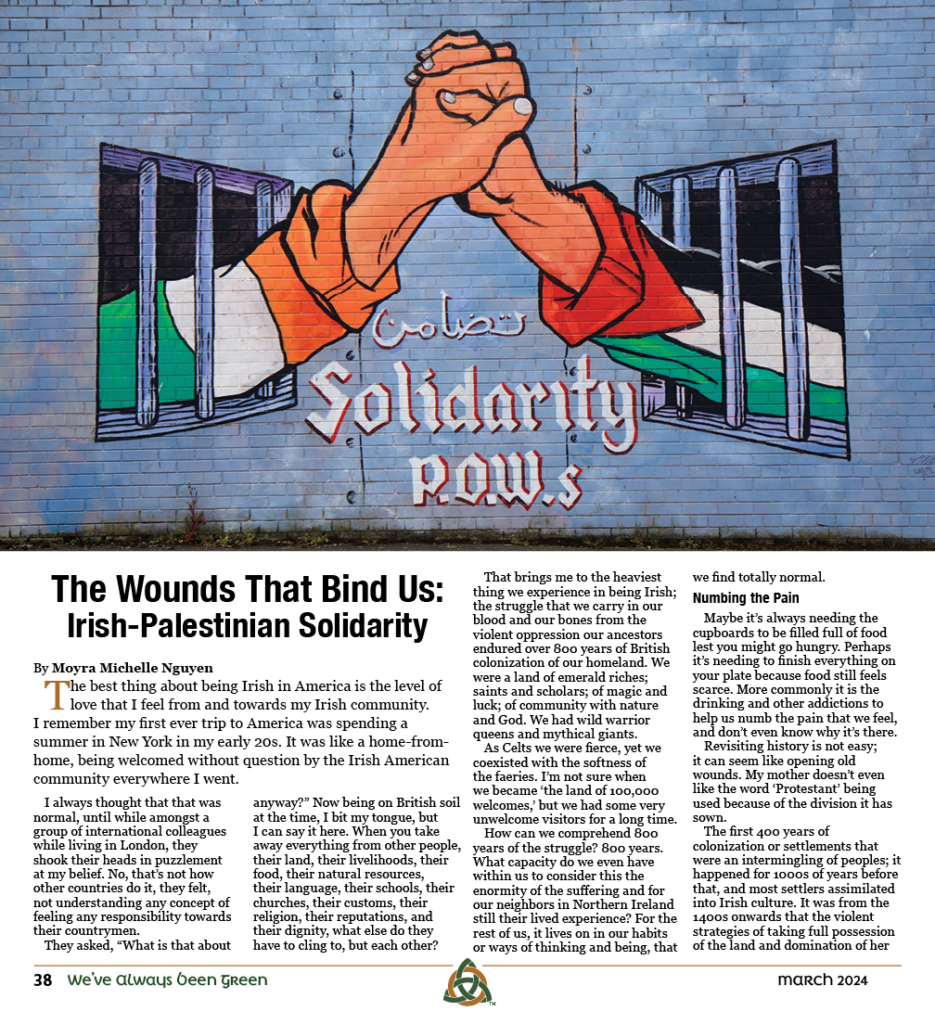

Irish Palestinian Connection

The Irish-Palestinian connection isn’t obvious from the outset. Thousands of miles apart, we look different. We speak differently, but we share some very common stories and bonds.

They are devout in their faith and center family and community in their lives. They just want to live in peace on their lands and carry on the nationhood and customs of their ancestors.

They never asked for the war and occupation that was thrust upon them by Englishmen thousands of miles away. These stories are our stories because we are them and they are us, on a more modern and different timeline.

As we were gaining our hard-won independence from a British Empire that the sun was finally setting on, their lives were about to be torn asunder by that very same force. The British Balfour Declaration of 1917 expressed support for a small political faction of Zionist European Jews who believed that Palestine was their homeland and revival of the Old Testament name of ‘Israel.’

It wasn’t much of a stretch for Britain to support their claim of a foreign land as their own. This political support gave great legitimacy to their cause, elevating an obscure political idea into a colonial master plan.

Meanwhile, back closer to home, the ‘Ireland problem’ persisted. The Irish people were conducting a quiet uprising through civil disobedience. This approach was difficult for the British because they needed violence to justify their usual methodical and brutal punishment.

Violence arrived on both sides. The Irish, with not much else to lose, took up arms and created the Irish Republican Army (IRA). They were ready to take the difficult actions needed to end the occupation.

Come Out Ye Black and Tans

The British met this with the Black & Tans, a paramilitary-style policing unit still despised to this day. Their job was to create chaos, disorder, and terror among the Irish civilian population, using any means to quell the uprising.

They conducted raids, committed arson, and left a trail of destruction throughout the country. Highlights include burning Cork City to the ground and massacring GAA fans in their seats as they watched a Gaelic match at Croke Park.

After much bloodshed, the Anglo-Irish treaty was signed in July of 1921, and the Black and Tans could finally leave our shores. With a honed skillset for state-sanctioned terror, where would Winston Churchill send them next?

That’s right, their new trenches became Palestine, where Britain had engineered political power for themselves following WWI. A gloomy future was being carved out by British colonizers stealing Palestinian land from under their feet under ‘Mandate Palestine.’

Voyagers to Ireland traveled a long way to get to Ireland, often it being a last stop. The Middle East was very different. It was a melting pot of cultures and a hub for global merchants passing through for as long as history has been recorded. Christians, Muslims, and Jews lived together peacefully on these lands for thousands of years.

The return of Jews to this area in the early 1900s was at first just another flow of people moving peacefully through the region. Many Jews found safety there during the times of the terrible Holocaust.

However, where we find Britain, we find conflict; their destabilization methods quickly wreaked chaos and inequality in the entire region. Now Britain wanted out of the Middle East but was not willing to give up control.

Ronald’s Stores, who was the British Military Governor for Mandate Palestine at the time, is quoted as saying, “We’re trying to create a little loyal Jewish Ulster in a sea of potentially hostile Arabs.”

They took their remorseless approach to Ireland and planted it right into the resource-rich Middle East, using Jewish Zionists to hold the reins of colonial power instead of their men. Occupation by proxy was afoot.

A Gorta Mor

Ireland’s great disaster is called “A Gorta Mor” (1845 to 1851), which is translated in sentiment as ‘The Great Hunger’ but the more literal translation from Gaeilge is “The Big Hurt.” Hunger as gaeilge is ‘Ocras’.

The Great Hunger is now widely acknowledged as an attempted genocide of the Irish people. The Irish were left to die after the potato crop failed for many consecutive years, while all the other food was exported to Britain.

The Palestinian great disaster occurred in 1948, and is called “the Nakba,” which translates as “The Catastrophe.” The UN estimates that upwards of 700,000 Palestinians were expelled from their homes and ancestral lands at this time, and millions more since.

Jewish Zionists declared this new country, called Israel.

(Note: Jewish Zionists are not to be confused with or used as a synonym for people of the Judaic faith. Zionists are a sect of political belief that believes in the Israel project, using Judaism in much the same way that Europeans used Christianity as they colonized the world in earlier centuries. Many Jews are highly opposed to the Israeli project and recognize it as a trauma response to the devastation of the holocaust).

The Catastrophe that started in 1948 has never ended. War after war has claimed more and more of the indigenous lands and sacred lives of the Palestinians. The current escalation of this war of occupation has been ongoing since October 7th, 2023, after an offensive by the Palestinian freedom fighters Hamas.

At the time of this writing, the death toll was estimated at 30,000 people. That’s almost the entirety of County Leitrim wiped out. That is Westlake, Ohio emptied of all its citizens. The loss is unimaginable, yet it is very much the reality that we are living with here in 2024.

An ever-diminishing number of brave Palestinian journalists survive to document the brutality of this war from their smartphones. This is the first war in history where the media and government do not get to control what we see and know about these billion-dollar wars. Veterans who have seen so much will deeply understand what this means.

Every day, images of savagery are posted as pleas for help, with questions like, ‘Does anyone care?’ I have seen videos of bodies being blown apart; hospitals being bombed with wards of babies in their incubators; children being pulled out of rubble; and women shot while carrying white flags and falling, with their children’s hands still in theirs. Those not killed by bombs are getting sick and being starved to death, while food and aid sit at the border, unsafe to enter this bombarded territory.

And the men, I see these brave men run to the sites of each of these blasts and use their bare hands to retrieve dead and barely alive bodies from the rubble. I ask, how are these men to return to a normal life after touching this much death and destruction?

In our Irish communities, I see that men have been the most affected by our legacy of colonization, or perhaps that it is just more pronounced. Men are way more likely to suffer from alcoholism and other addictions, less likely to be able to ask for help, more likely to suffer in stoic silence, more likely to commit suicide, and more likely to suffer from a host of chronic conditions.

No One Shows You How to Be Free

Outside of the bloodshed that accompanies war and colonialism, there is the loss of dignity that comes with stripping a man of his ability to provide a safe home and put food on the table for his family. We women didn’t come out unscathed either; emotional support systems are easier to find to help us process these old emotions. No one shows you how to be free.

Tears don’t come easily to me. I grew up in a stoic Irish family much like yours, I’m sure. Perhaps when a culture carries so much pain and sadness, it can seem like allowing just a few tears could easily turn into a tsunami; if the floodgates open, they might never be able to shut again.

But I weep as I watch the scenes of destruction and death, for I know it in my blood and my bones. I not only grieve for these sacred Palestinian lives being lost by the hundreds every day, but I grieve for myself too. I grieve for all my ancestors and your ancestors who lived and died through wars waged for land and power.

And I grieve for all the forgotten, past, present, and future, who have been touched by colonization and war. I shake my head and ask, “How is this still happening?”

When I look into the eyes of our Palestinian brothers and sisters living here as immigrants and refugees, I think these are the only eyes that can see us Irish and understand us. To many, we are simply more white Europeans who came to America because of privilege and choices, not indigenous people of the lands of Eireann, whose land was stolen by people who looked just like us.

Did you know that in 1847, as the famine was ravishing Ireland, the Choctaw Nation, who had only recently arrived across the tragic Trail of Tears and Death, gathered a donation equivalent to $5,000 to support the Irish? It often seems to be the ones with so little will give so much. Other nations and institutions including the Ottoman Empire, which ruled over Palestine at the time sent $1,000 and ships full of food and aid in response to the suffering, an amount limited by the British crown for self-serving reasons.

I was taught in school that colonialism was over. Yet here we are. The border that separates the Republic of Ireland from the six counties of Northern Ireland still exists. Dotted all around the Northern Ireland streetscape are murals dedicated to Palestine by the Catholics of Northern Ireland and some dedicated to Israel by the Protestant Loyalists.

I believe that Northern Ireland has the right to self-determination and we get to support that in a way that empowers those communities that have been waiting so long for peace. For far too long, decisions have been made by people who don’t live on the lands that those decisions are being made about.

I believe Palestine has the same right. We can use our power and privilege to help those who continue to go through what we went through. Palestinians don’t need to suffer for 800 years like we did.

We need to find ways to let them know that they are not alone or forgotten. There have been many protests throughout this country, in Ireland, and all over the world. The Irish have been one of Palestine’s most vocal supporters in the Western world.

Irish lawyers are part of the legal team that partnered with international world governments in the South African-led International Court of Justice, charging the Israeli government with genocide and other war crimes.

Our local and national politicians need to speak on our behalf. The spotlight of the world is on the plight of the Middle East and the morals of the Western world.

Will we look away like so many did, as we starved? Or do we reach out a hand and do everything we can to say, never again?

Jesus Wept

Thinking of the most famous Palestinian man in history, we must ask ourselves, what would Jesus do? And I’m sure from there we can find the right answer, and the courage and initiative to follow it through.

B’fheidir go tiocfaidh ar la e anois. (Maybe ‘our day will come’ is now).

If you would like to express your support locally in Cleveland to encourage your representatives at Cleveland City Council to call for a ceasefire, follow this link to sign your name. It will only take 1 minute.

Link: https://forms.gle/HXQS1vfQrYQxBmNn9

*Moyra Michelle Nguyen is a native of Sligo, Ireland. She has been living in Cleveland since 2011. She is a trauma healer helping people to overcome their pasts to mentally and physically feel better and to build better futures.