This month’s column will be in two parts: Part I will look at efforts by Ireland to secure recognition of the newly formed Irish Republic by the 1919 Paris Peace Conference. The second part will look at the efforts of Irish America to assist in gaining recognition on Ireland’s behalf.

World War I ended with the Armistice declared on November 11, 1918. The Paris Peace Conference convened in January 1919 at the Versailles Palace just outside Paris. The peace conference was called to establish the terms of peace after World War I.

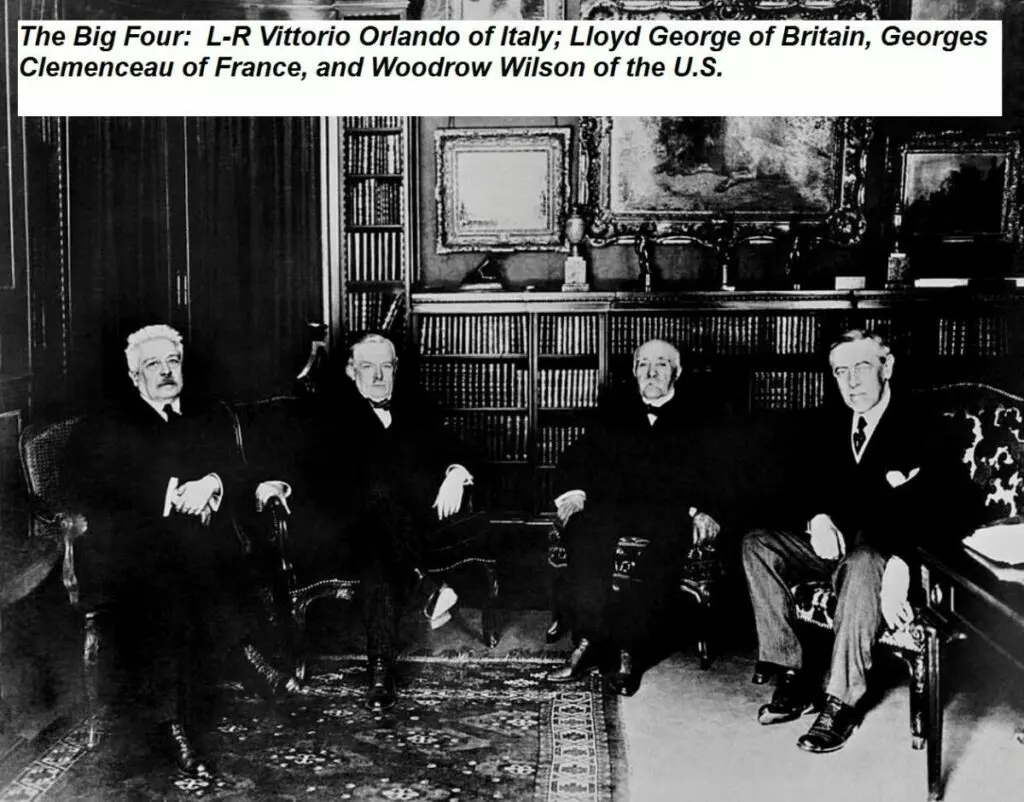

All though nearly thirty nations participated in the conference, the representatives of “The Big Four” (England, France, the United States, and Italy) dominated the proceedings and decision-making. French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau served as the Chairman.

Based on winning the majority of seats in the Irish election of December 1918, the elected Sinn Féin Representatives absented themselves from Parliament, established the First Dáil in January 1919, and declared the independent Irish Republic.

Éamon de Valera had been arrested in May 1918 by the British and escaped from Lincoln Jail in February 1919. Upon his return to Ireland, he was appointed the Príomh Aire by the First Dáil on April 1, 1919 (pron: preeve air-a, also called President of Dáil Éireann, or First Minister).

A League of Nations

In the U.S., President Woodrow Wilson was serving his second term in office. On January 8, 1918, Wilson delivered a speech, known as his Fourteen Points, wherein he laid out his administration’s long-term war objectives. Wilson also called for the establishment of an association of nations to guarantee the independence and territorial integrity of all nations – a League of Nations.

Wilson’s Fourteen Points emphasized the importance of “self-determination.” That is the legal right of people to decide their destiny in the international order.

Wilson later wrote: “Self-determination is not a mere phrase. It is an imperative principle of action, which statesmen will henceforth ignore at their peril. National aspirations must be respected.”

Self-determination was hopeful language for the Irish, who viewed it as an opportunity to gain recognition of their new republic by meeting with the Treaty negotiators. They began a diplomatic effort to lobby the conference to gain recognition for the Irish Republic.

In January 1919, Woodrow Wilson traveled to Europe to represent the U.S. at the Paris Peace Conference. He joined the other three of the “Big Four” allies who would run the conference.

It is important to note that while the stated purpose of World War I, as proclaimed by England and France, was “to make the world safe for democracy,” the treaty negotiations were not about democracy. The chief goals of England and France were to punish Germany for starting the war and divide up Germany’s colonial empire to the economic benefit of England and France. These goals clearly would not be compatible with Wilson’s Fourteen Points.

In January 1919, the Dáil appointed Dáil Member Seán T. O’Kelly as minister to France, with the assistance of George Gavan Duffy. They were to establish a consulate in Paris and begin petitioning the Treaty negotiators to allow participation and recognition of the Irish Republic.

Joining them was O’Kelly’s wife, Mary Kate (Ryan). She was a lecturer in French at University College Dublin and her language skills contributed significantly to the Irish diplomatic efforts.

First of the Small Nations

They established the consulate in a suite at the city’s five-star Le Grand Hotel. O’Kelly invited French journalists, parliamentarians, and writers to help publicize the Irish cause. Gavan Duffy said, “Ireland had every reason to expect rapidly to become recognized as the First of the Small Nations.”

Gavan Duffy had first traveled to Paris to join O’Kelly but was forced to leave France after being ordered to do so by the French President as a result of pressure from the British government. This left O’Kelly as the sole Irish representative in Paris to make the case for recognition.

Between February and June, O’Kelly appealed to Woodrow Wilson and French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau on behalf of “le parliament Sinn Féin” and the “Irish Republican Congress.” Diplomatic overtures, however, met with no reply from either Wilson or Clemenceau.

On February 24, 1919, O’Kelly delivered a letter to the Secretary of the Peace Conference in Paris which claimed the right of recognition of the Irish Republic and the admission of Ireland as a member of the League of Nations. This letter was also ignored, as were all of Kelly’s communications.

President Wilson, a Democrat, was no friend to the Irish (despite his claims of support at election time). He regularly spoke of his dislike for what he called “hyphenated Americans.”

In a 1919 speech, he said, “… any man who carries a hyphen about with him carries a dagger that he is ready to plunge into the vitals of this Republic whenever he gets ready. If I can catch any man with a hyphen in this great contest, I will know that I have caught an enemy of the Republic.”

Wilson’s dislike for the Irish stemmed from the fact that Irish American lobbyists had campaigned against the country’s entry into World War I. During the war, Wilson had launched a secret intelligence campaign throughout America, as the Wilson administration sought to discredit groups and label them anti-American, seeing as many as 47 Irish-Americans being detained and charged with violation of the Espionage Act during this period.

His relations with the country of Ireland were also stormy. Wilson was controlled by the British, who declared that the problems in Ireland were an internal matter of the British and none of America’s business.

So, it appeared that the Irish were getting boxed out by the Big Four at the peace conference. O’Kelly was getting nowhere in his efforts at diplomacy.

De Valera realized that it was time to utilize Irish-America in the cause of recognition. In June 1919, De Valera headed to the U.S. on a speaking tour to gain support (and financial contributions) from Irish-America.

Next month will look at De Valera’s trip to America, as well as, Irish-American efforts to further lobby President Wilson and the Paris Peace Conference.

Find this column and others from the [month] 2023 issue here!

J. Michael Finn

*J. Michael Finn is the Ohio State Historian for the Ancient Order of Hibernians and Division Historian for the Patrick Pearse Division in Columbus, Ohio. He is also past Chairman and Life Member of the Catholic Record Society for the Diocese of Columbus, Ohio. He writes on Irish and Irish-American history; Ohio history and Ohio Catholic history. You may contact him at [email protected]

ends