“He was a lamp, blazing with the light of wisdom.”

The monastic way of life, which began in Egypt in the 3rd century, was introduced into Ireland by St. Patrick. He wrote of consecrating, “The sons and daughters of the leaders of the Irish are seen to be monks and virgins of Christ!” Monastic communities in the strict sense, involving vows, complete seclusion and discipline, owes its origins in Ireland to St. Enda of the Aran Islands.

St. Enda, after receiving his training and ordination from St. Ninian’s monastery at Whithorn Abbey in Scotland, founded his own monastery at Killeaney on Inis Mór, the largest of the Aran Islands off the western coast of County Galway. It was founded in about 484 and it is generally regarded as the first Irish monastery.

St. Enda began Killeaney with about 150 disciples. After its founding he also established a monastery in the Boyne Valley, and several others across Ireland. Along with St. Finnian of Clonard, Enda is known as the Father of Irish Monasticism.

One of Enda’s early pupils was St. Ciarán (Pron: keer-an), born about 516 at Rathcroghan, County Roscommon, Ireland. His father was a carpenter and chariot maker.

As a boy, Ciarán worked as a cattle herder. He became a student of St. Finian’s at Clonard and in time became a teacher. St. Colmcille of Iona said of Ciarán, “He was a lamp, blazing with the light of wisdom.”

The Twelve Apostles of Ireland

Ciarán became known as one of the Twelve Apostles of Ireland. The Twelve Apostles were twelve early Irish monastic saints of the sixth century who studied under St. Finnian at his monastery school at Clonard Abbey in County Meath.

In about 534, Ciarán left Clonard for Inis Mór, where he studied under St. Enda of Aran, who ordained him a priest and advised him to build a church and monastery in the middle of Ireland. About 541 Ciarán travelled to the monastery of St. Senan on Scattery Island, an island at the mouth of the Shannon River off the coast of Kilrush, County Clare.

In 544, Ciarán traveled further up the Shannon to Clonmacnoise. There he and ten companions founded the Monastery of Clonmacnoise. In Irish, Clonmacnoise is Cluain Mhic Nóis (Pron: cloo-in vik no-sh) meaning The Meadow of the Sons of Nós.

The monastic ruin is situated in County Offaly, on the left bank of the Shannon River, south of Athlone. The strategic location of the monastery helped it become a major center of religion, learning, craftsmanship, pilgrimage and trade.

As abbot, Ciarán worked on the construction of the first buildings of the monastery; however, he died in 549 of a plague, in his early thirties. By the year 700, Clonmacnoise was surrounded by a large, thriving settlement. It was referred to at the time as Ciarán’s Shining City.

This lay community worked and farmed the large estates held by Clonmacnoise. There were masons, carpenters, metalworkers, and craftspeople of all kinds.

The Book of the Dun Cow, the earliest Irish illuminated manuscripts in existence today which is written almost entirely in Irish, was compiled by the monks at Clonmacnoise. It is known in Middle Irish as Lebor na hUidre (Pron: lay-bor nah hud-re ) or Book of the Dun Cow, so called because the original vellum upon which it was written was supposedly taken from the hide of the famous brown cow owned by St. Ciarán.

Compiled about 1100 by learned Irish monks at the monastery of Clonmacnoise from older manuscripts and oral tradition, the Book of the Dun Cow is a collection of factual material and legends that date mainly from the 8th and 9th centuries.

The Irish Ulster Cycle

It also contains some religious texts. It includes a partial text of The Cattle Raid of Cooley or Táin Bó Cúailnge (Pron: tawn bow coole-in-ya). It is the longest tale of the Irish Ulster Cycle and the one that most nearly approaches epic stature, as well as other descriptions of the conflict between Ulster and Connaught.

The monastery was not without its troubles. Being next to the Shannon River, the monastery provided easy access to its enemies. Clonmacnoise was burned down thirteen times between 722 and 1205; sacked eight times by Viking raiders who sailed up the Shannon; attacked twenty-seven times by native Irishmen in various feuds and disputes between 832 and 1163; and attacked six times by Anglo-Norman between 1178 and 1205. In 1552 the English garrison at Athlone destroyed and looted Clonmacnoise for the final time, leaving it in ruins.

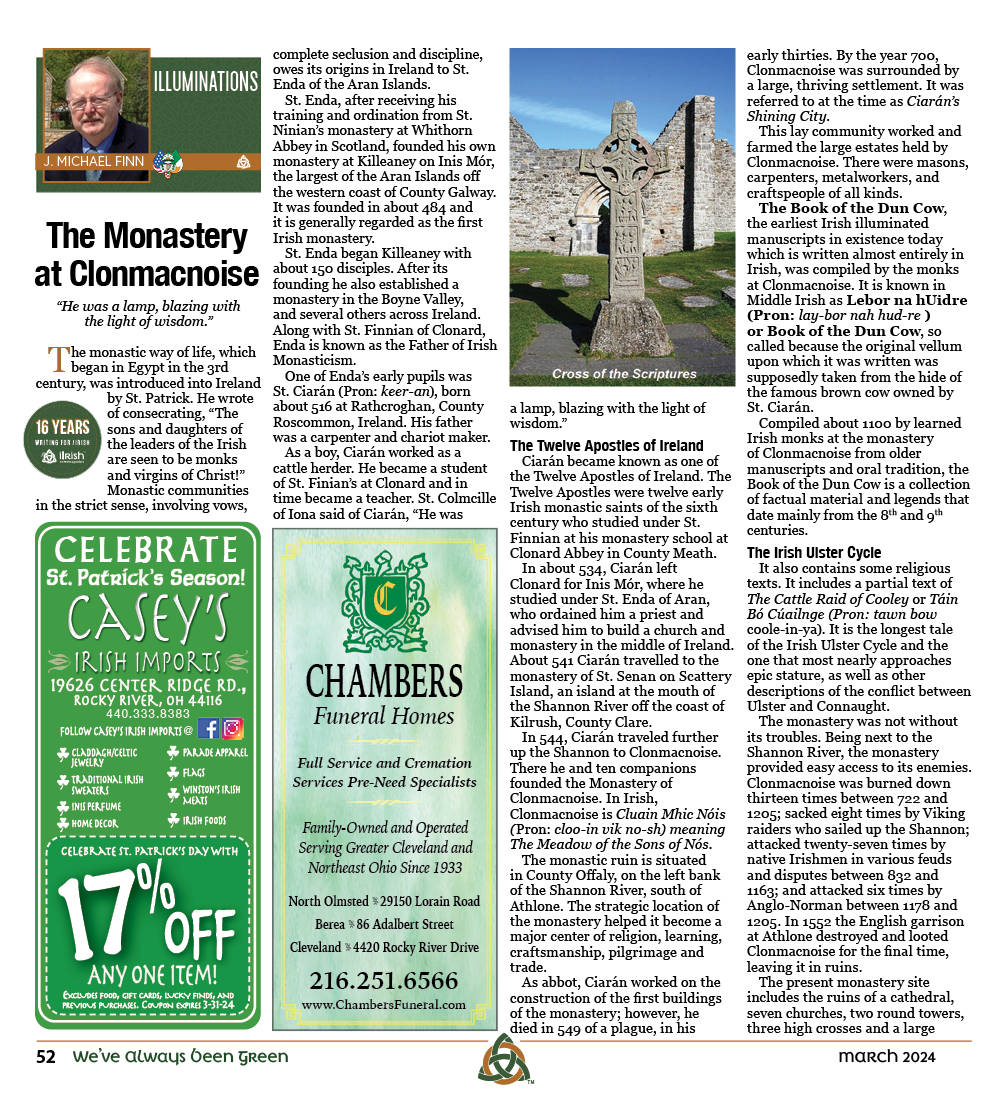

The present monastery site includes the ruins of a cathedral, seven churches, two round towers, three high crosses and a large collection of Early Christian grave slabs. A few of the notable things to see at Clonmacnoise include the following:

The Cross of the Scriptures – one of Ireland’s finest high crosses in Ireland, the cross was carved from one solid block of Clare sandstone about the year 900 and stands slightly over 13 feet tall. The carved panels represent Christ’s crucifixion, death and resurrection.

The large base, in the form of a pyramid, is thought to represent The Hill of Calvary where Christ was crucified, while the capstone represents the Holy Sepulcher. The cross has one panel showing St Ciarán and King Dermot erecting the corner-post of the church at Clonmacnoise. The original cross was moved inside the new Visitor Center in 1993 to protect it from weathering, while an exact replica is displayed on the original site.

O’Rourke’s Tower – stands in the northwest corner of the monastic complex. It is quite difficult to date when it was actually built. The tower gets its name from the builder Fergal O’Rourke, who died in 964 AD.

The tower is superbly built and unusually wide. It was struck by lightning in 1135, which accounts for the tower only being 63 feet tall. It is estimated to be just two-thirds of its original height.

Clonmacnoise was largely abandoned by the end of the 13th century. Today, Ciarán’s monastery on the Shannon welcomes about 150,000 visitors per year. Pope John Paul II paid a visit to the site in 1979 during his trip to Ireland.

Find this column and others here!

J. Michael Finn

*J. Michael Finn is the Ohio State Historian for the Ancient Order of Hibernians and Division Historian for the Patrick Pearse Division in Columbus, Ohio. He is also past Chairman and Life Member of the Catholic Record Society for the Diocese of Columbus, Ohio. He writes on Irish and Irish-American history; Ohio history and Ohio Catholic history. You may contact him at FCoolavin@aol.com

ends