Examining the Battle of Vinegar Hill through the Lense of a Wargame

By Stephen L. Kling, Jr.

As many Irish are keenly aware, the Battle of Vinegar Hill was a climactic battle in the Irish Rebellion of 1798. The rebellion as well as the battle are part of the fabric of Irish history and the treatment of the participants in the battle and of civilians continues to evoke strong feelings to this day.

The battle was the largest of the rebellion. The Irish massed their troops and made a camp on Vinegar Hill across the Slaney River from Enniscorthy. Some accounts say there were 20,000 people on the hill but that may have included many women and children who had lost their homes or were following their men.

Gerard Lake was the British general in charge of suppressing the rebellion on the south. He devised a plan of five converging columns to attack and surround Vinegar Hill and Enniscorthy to crush the rebellion once and for all.

One column under General John Moore, later of Peninsular War fame, was delayed by an attack of Irish rebels under Father Philip Roche. A second column under General Francis Needham, hamstrung with supply wagons and carriages, failed to arrive on time. A third column attacked Enniscorthy and two more assaulted Vinegar Hill.

The fighting at Enniscorthy was fierce. The Irish were led by William Barker, an accomplished soldier who had fought with the French. The main bridge of Enniscorthy across the Slaney River was renamed in his honor.

The fighting at Vinegar Hill was also hotly contested and many women joined in the defense, but eventually, the British forced the Irish off the hill with their superior artillery and replaced the Irish flag with a British one on the top of a windmill on Vinegar Hill. As Needham’s forces failed to arrive, a gap in the line toward Wexford allowed the Irish to escape to the mountains and carry on the war.

New Light on Battle of Vinegar Hill

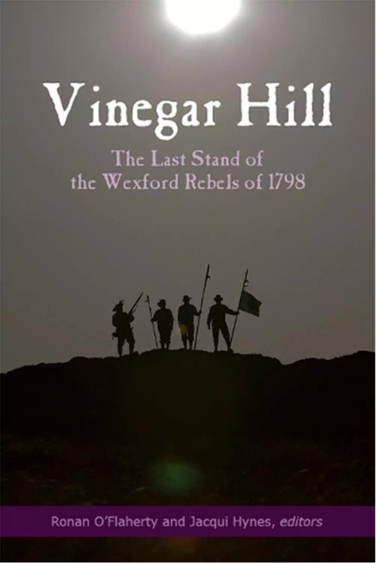

Recent scholarly research has shed new light on the battle and focused some new interest in its underlying history. Vinegar Hill: The Last Stand of the Wexford Rebels of 1798, which was edited by Ronan O’Flaherty and Jacqui Hynes and published by Four Courts Press in 2021, includes research by a multidisciplinary team of archaeologists, historians, folklorists, architectural historians, and military specialists.

The book provides fascinating new insights into what happened at Vinegar Hill on that fateful day in June 1798. As part of a popular effort, the National 1798 Rebellion Centre in Enniscorthy, Wexford County was saved from local development and reopened in 2022 with all new exhibits about the history of the battle and the rebellion in general. An annual reenactment, “the Longest Day Commemoration” is also organized in Enniscorthy.

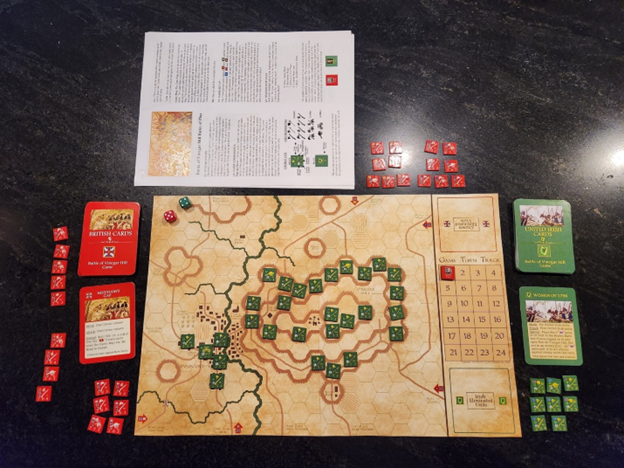

In 2014, I formed The Historical Game Company, LLC, as a part-time operation to publish low-complexity games based on historical battles. The games are intended to utilize a small format and attempt to interest players in the underlying history. They include an 11” x 17” map, between 48 and 64 counters (generally military units that participated in the battle), 20 historically relevant event cards that drive game play, and a 4-page rulebook.

The map has a hex grid imposed upon it to the movement of the units during game play. Each copy of the rules contains the following statements: “No political agenda or condemnation or glorification of any historical situation upon which this game is based is intended. This is a historical game to explore and learn about tactics, problem solving and history- period. The hope is that game players will want to know more about this interesting history which is why a further reading section is added.”

In the early fall of 2024, I set my sights on the Battle of Vinegar Hill. The battle had always been one I was interested in adapting into a game because I had an ancestor who emigrated from Limerick, Ireland in the early 1800s. My goals for the game were to do justice to the history, in a non-biased way, to allow players to learn more about the battle and to enable players to explore some “what ifs” and alternative strategies to see if they can change history in a game setting.

I am the author of several military history books on 18th century wars and the co-curator and designer of The American Revolutionary War in the West Museum exhibit, which opened in 2021, so I am aware of the importance of in-depth research. While research for a game design cannot match the thoroughness required for a scholarly book, reading the primary sources first was a must to get a feel for the battle and the viewpoint of participants, particularly with an eye toward the selection of game cards. I also read the Vinegar Hill book, which provided further and new ways to consider the battle.

Historical Accuracy

While historical accuracy is an important element in game design, it can be a challenge to fit it facilitate in the constraints of the system (as such limits are imposed by my publisher) while making it a challenging game and not a rote simulation. Developing each game generally starts with the map, which requires not only a study of source material but also a search for period maps.

The geography usually must be adjusted slightly to fit on hexagonal map and to provide for game flow. Important features such as Duffry Gate, Enniscorthy Castle, the Vinegar Hill windmill, Beale’s Barn, the Slaney River, the all-important Enniscorthy Bridge (now the William Barker Bridge) and Vinegar Hill, which dominates the map, all need to be depicted for a historical feel.

The unit counters must reflect the historical forces that took part in the battle, which requires looking for orders of battle, or if those are unavailable, reading the reports of the military leaders involved. While I was unable to find any detailed order of battle for Vinegar Hill, I used the correspondence of British Generals Lake and Moore, the Musgrave and Maxwell histories, and the Vinegar Hill book to develop the unit counter mix.

While an exact listing of the regiments and battalions is elusive, the general number of troops involved is discussed in several sources with some small discrepancies. The final game includes counters representing the few United Irish musket armed men, a plethora of pikemen, a couple women irregulars – who according to author Sir Jonah Barrington, “fought with fury” at the battle, and a few artillery units including a cannon mounted on a cart which was used by William Barker at Enniscorthy. For the British (referred to as Crown forces in the game), artillery, light battalions, dragoons, militia, fencibles and yeoman units round out the British side.

Game card development came next, with some of the usual move and attack limitations included in the cards, which I generally chose after reading the histories and based on my game design experience. Card names and special events listed in each card are based specifically on the history, which can aid or in some cases limit a player’s options on a particular turn.

The cards need to evoke the history of the battle and incorporate significant real-life factors. For the Battle of Vinegar Hill, the cards feature Irish pikemen charges, experienced British generals, women who participated in the fighting, and the possibility of forces under British General Needham or Father Philip Roche showing up as expected – to name a few. Each player only has one card drawn blindly each turn, so the twenty game cards are an important part of the game and allow for varied outcomes of game flow and results depending on how players take advantage of card opportunities and deal with card restrictions.

Once preliminary designs for the map, counters and cards are developed, the next step is to have a playtest copy printed to see how the game works and what adjustments or special rules might be needed. All my games share the same basic rules, but there are always special rules tied to the specific battle the game is based on.

The victory conditions (how a player wins a game) usually need to be fixed after some playtesting, to make sure the gameplay remains in line with the historic objectives. Generally, victory conditions coincide with occupying or controlling certain key locations on the map. For example, in this case, one would be the Vinegar Hill windmill hex which was the center of the United Irish camp. Of course, dice are part of the game mechanics, which further add a certain amount of unpredictability to each game.

Something new I tried with this game was to create a separate Facebook page, where interested people could follow along in the game design, development, playtest process, and historical considerations, and contribute comments or ask questions. The page can be found at this link: https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=61564653026253.

Much like games and ongoing historical research in the United States on key battles such as Yorktown and Gettysburg, the Battle of Vinegar Hill should be similarly well known and not forgotten.

Playtesting of the game should be complete in the next few months with a publication expected either the end of 2024 or early 2025.

Further Reading

Further Reading:

Ronan O’Flaherty and Jacqui Hynes, eds., Vinegar Hill: The Last Stand of the Wexford Rebels of 1798 (Four Courts Press, Dublin, Ire.: 2021).

Dáire Keogh and Nicholas Furlong, The Women of 1798 (Four Courts Press, Dublin, Ire.: 1998).

Riccardo Masini, Historical Simulation and Wargames: The Hexagon and the Sword (CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL: 2024).

Sir Richard Musgrave, Memoirs of the Irish Rebellion of 1798, 3rd ed. (Round Tower Books, Fort Wayne, Ind.: 1995)

*Stephen L. Kling, Jr. is a practicing attorney and historian who has authored five military history books, mostly covering the American Revolutionary War in the western theater. He was the primary consultant for the award-winning House of Thunder documentary based on one of his books, and the designer and co-curator of the American Revolutionary War in the West Museum Exhibit.