When you find yourself in Salisbury, three miles from the UNESCO world heritage site, that is Stonehenge, well, you must go. We made this decision despite a warning from a tourist at the Amer- ican-style strip mall that sprang up outside lovely medieval Salisbury, “Stone- henge, underwhelming, it’s just a pile of rocks”.

Off we went. If you had no idea where Stonehenge was, a safe bet would be to follow the line of traffic liberally sprinkled with camper vans and mega-buses. As we inched along the decently wide road, rolling, bucolic countryside gave way to a flat, grassy plain.

Finding Stonehenge

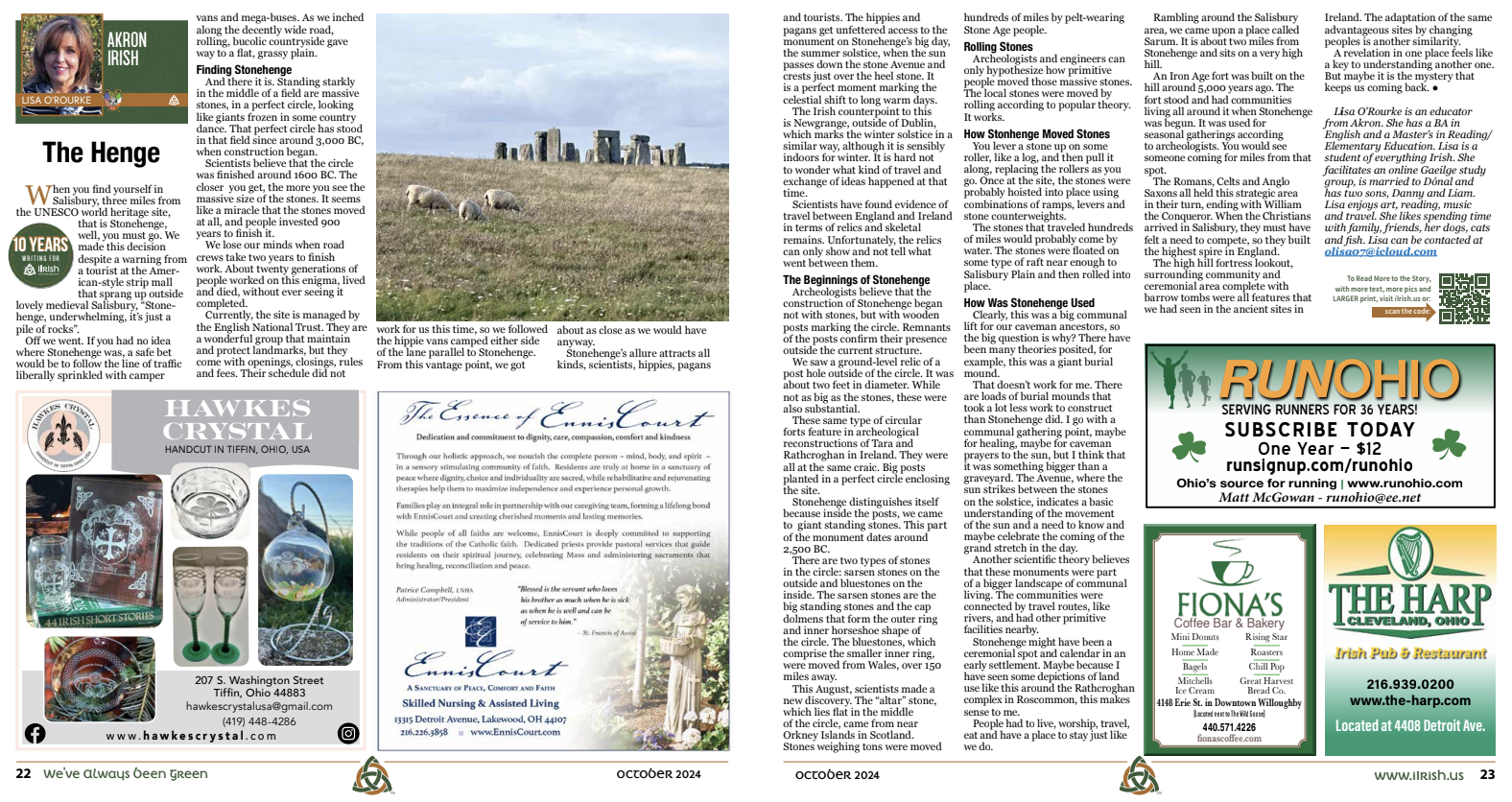

And there it is. Standing starkly in the middle of a field are massive stones, in a perfect circle, looking like giants frozen in some country dance. That perfect circle has stood in that field since around 3,000 BC, when construction began.

Scientists believe that the circle was finished around 1600 BC. The closer you get, the more you see the massive size of the stones. It seems like a miracle that the stones moved at all, and people invested 900 years to finish it.

We lose our minds when road crews take two years to finish work. About twenty generations of people worked on this enigma, lived and died, without ever seeing it completed.

Currently, the site is managed by the English National Trust. They are a wonderful group that maintain and protect landmarks, but they come with openings, closings, rules and fees. Their schedule did not work for us this time, so we followed the hippie vans camped either side of the lane parallel to Stonehenge. From this vantage point, we got about as close as we would have anyway.

Stonehenge’s allure attracts all kinds, scientists, hippies, pagans and tourists. The hippies and pagans get unfettered access to the monument on Stonehenge’s big day, the summer solstice, when the sun passes down the stone Avenue and crests just over the heel stone. It is a perfect moment marking the celestial shift to long warm days.

The Irish counterpoint to this is Newgrange, outside of Dublin, which marks the winter solstice in a similar way, although it is sensibly indoors for winter. It is hard not to wonder what kind of travel and exchange of ideas happened at that time.

Scientists have found evidence of travel between England and Ireland in terms of relics and skeletal remains. Unfortunately, the relics can only show and not tell what went between them.

The Beginnings of Stonehenge

Archeologists believe that the construction of Stonehenge began not with stones, but with wooden posts marking the circle. Remnants of the posts confirm their presence outside the current structure.

We saw a ground-level relic of a post hole outside of the circle. It was about two feet in diameter. While not as big as the stones, these were also substantial.

These same type of circular forts feature in archeological reconstructions of Tara and Rathcroghan in Ireland. They were all at the same craic. Big posts planted in a perfect circle enclosing the site.

Stonehenge distinguishes itself because inside the posts, we came to giant standing stones. This part of the monument dates around 2,500 BC.

There are two types of stones in the circle: sarsen stones on the outside and bluestones on the inside. The sarsen stones are the big standing stones and the cap dolmens that form the outer ring and inner horseshoe shape of the circle. The bluestones, which comprise the smaller inner ring, were moved from Wales, over 150 miles away.

This August, scientists made a new discovery. The “altar” stone, which lies flat in the middle of the circle, came from near Orkney Islands in Scotland. Stones weighing tons were moved hundreds of miles by pelt-wearing Stone Age people.

Rolling Stones

Archeologists and engineers can only hypothesize how primitive people moved those massive stones. The local stones were moved by rolling according to popular theory. It works.

How Stonhenge Moved Stones

You lever a stone up on some roller, like a log, and then pull it along, replacing the rollers as you go. Once at the site, the stones were probably hoisted into place using combinations of ramps, levers and stone counterweights.

The stones that traveled hundreds of miles would probably come by water. The stones were floated on some type of raft near enough to Salisbury Plain and then rolled into place.

How Was Stonehenge Used

Clearly, this was a big communal lift for our caveman ancestors, so the big question is why? There have been many theories posited, for example, this was a giant burial mound.

That doesn’t work for me. There are loads of burial mounds that took a lot less work to construct than Stonehenge did. I go with a communal gathering point, maybe for healing, maybe for caveman prayers to the sun, but I think that it was something bigger than a graveyard. The Avenue, where the sun strikes between the stones on the solstice, indicates a basic understanding of the movement of the sun and a need to know and maybe celebrate the coming of the grand stretch in the day.

Another scientific theory believes that these monuments were part of a bigger landscape of communal living. The communities were connected by travel routes, like rivers, and had other primitive facilities nearby.

Stonehenge might have been a ceremonial spot and calendar in an early settlement. Maybe because I have seen some depictions of land use like this around the Rathcroghan complex in Roscommon, this makes sense to me.

People had to live, worship, travel, eat and have a place to stay just like we do.

Rambling around the Salisbury area, we came upon a place called Sarum. It is about two miles from Stonehenge and sits on a very high hill.

An Iron Age fort was built on the hill around 5,000 years ago. The fort stood and had communities living all around it when Stonehenge was begun. It was used for seasonal gatherings according to archeologists. You would see someone coming for miles from that spot.

The Romans, Celts and Anglo Saxons all held this strategic area in their turn, ending with William the Conqueror. When the Christians arrived in Salisbury, they must have felt a need to compete, so they built the highest spire in England.

The high hill fortress lookout, surrounding community and ceremonial area complete with barrow tombs were all features that we had seen in the ancient sites inIreland. The adaptation of the same advantageous sites by changing peoples is another similarity.

A revelation in one place feels like a key to understanding another one. But maybe it is the mystery that keeps us coming back.

Lisa O’Rourke is an educator from Akron. She has a BA in English and a Master’s in Reading/ Elementary Education. Lisa is a student of everything Irish. She facilitates an online Gaeilge study group, is married to Dónal and has two sons, Danny and Liam. Lisa enjoys art, reading, music and travel. She likes spending time with family, friends, her dogs, cats and fish. Lisa can be contacted at [email protected]

Lisa O’Rourke is an educator from Akron. She has a BA in English and a Master’s in Reading/Elementary Education. Lisa is a student of everything Irish. She facilitates an online Gaeilge study group. She is married to Dónal and has two sons, Danny and Liam. Lisa enjoys art, reading, music and travel. She likes spending time with family, friends, her dogs, cats and fish. Lisa can be contacted at [email protected].