By Sue Mangan

“Hidden under wild ferns on Howth. Below us bay sleeping.

No sound. The sky. A goat. No-one. High on Ben Howth rhododendrons

a nannygoat walking surefooted dropping currants.”

(James Joyce: Ulysses)

In my mind’s eye I am sitting on the edge of an old water trough in the field by my Uncle Pat’s milking barn. I have been told to sit and watch that the trough does not spill over with water. Used to my presence, the calves meander by, awkwardly bucking into one another. Flies buzz around their crusty hind quarters.

Singing Kansas’ “Dust in the Wind,” I pretend that I live in this meadow, friend to the calves, the June Bugs, the barn cats, the dogs, the goat. With all my heart, I believe that I can talk to the animals. A veritable Dr. Doolittle, I can soothe the creatures with my voice. I am alone, but not lonely.

Quite happy with my singing, my imagination, the calves, and buzzing field insects, I do not realize the trough is overflowing until rivulets of wet manure and dirt begin to pool around my green Adidas tennis shoes.

Hoping against hope that the relentless July sun will dry up the small flood before my uncle leaves the barn, I hurry to the water pump, faded red from the Ozark sun, and shut it down.

The calves look at me with large eyelash-framed brown eyes and softly mewl when my uncle comes to find me. Toothpick dangling from his mouth, he looks at me and then the drying moat by my feet. “Hey,” my uncle drawls, “Let’s find you another job, alright?”

And so, my time spent on the farm was comprised of jobs to keep me busy and out of the way of farmer work. I was often put to the task of feeding the calves with oversized baby bottles and scooping feed down the chute to cows trapped in the milking stalls.

How I loved to talk with the animals, especially to a goat that I named Pierre. I was put to the task of milking Pierre before suppertime. It was only in my later years that I realized Pierre was not the most apt name for a goat producing milk, but alas the innocence of youth.

My mother often told me of her own childhood farm pet: Buck Buck the goat. Now, Buck Buck was all mischief, a regular Huckleberry Finn on the farm.

Buck Buck bucked my grandmother as she hung the laundry to dry in the hot sun. Shaking his head, Granddad laughed and laughed. One fateful day, Buck Buck, all fire and energy, chose to buck the wrong farmer. Milk cans went flying. My mother never knew exactly what happened to Buck Buck after that unfortunate event, but she reckoned that he became a fine Easter meal.

I would never make it as a farmer because in my heart I would love all the birds and beasts as family members. Never would I consider assigning Buck Buck a fatal sentence because he was simply doing what he does best, bucking.

Animals are among our greatest treasures. Imagine a spring morning without birdsong, an oak without a squirrel, the sea without fish. During my past visit to Ireland, I learned of a species that has roamed the rugged mountains and hills of Ireland since the Neolithic Age. Today, this animal is near extinction: the Old Irish Goat.

Old Irish Goat

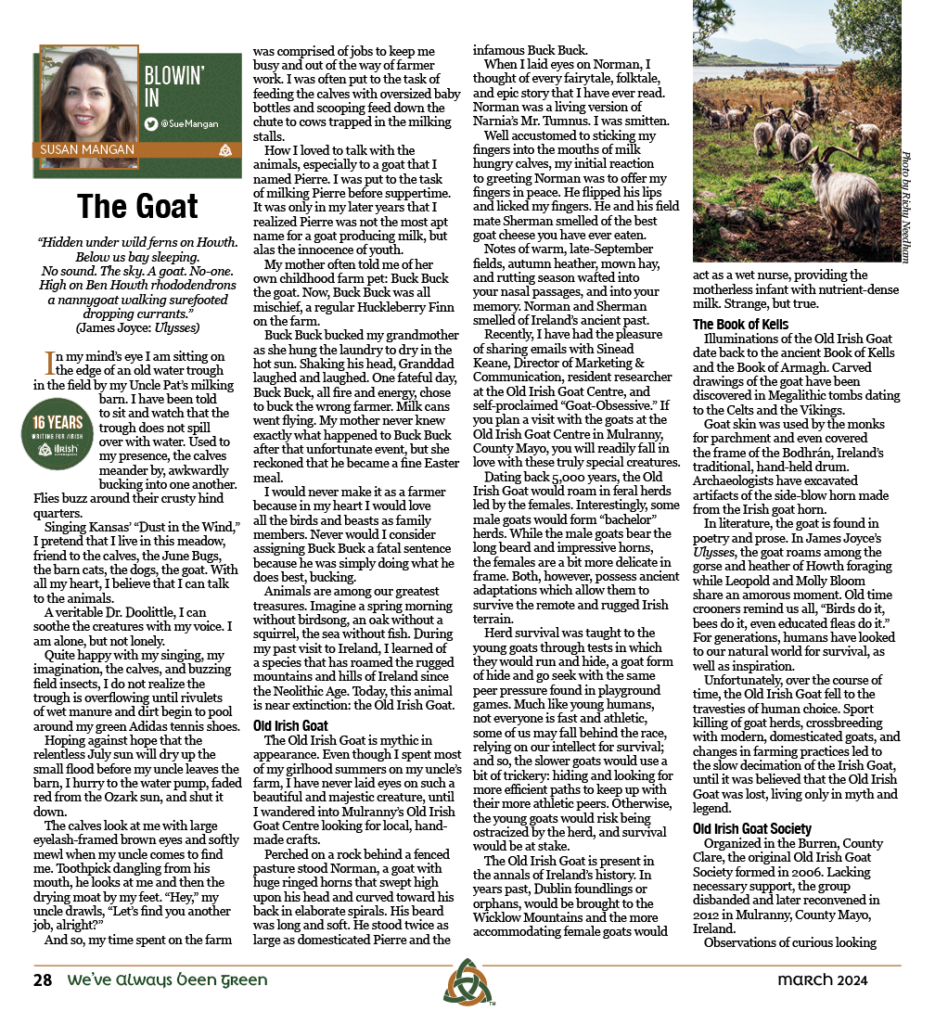

The Old Irish Goat is mythic in appearance. Even though I spent most of my girlhood summers on my uncle’s farm, I have never laid eyes on such a beautiful and majestic creature, until I wandered into Mulranny’s Old Irish Goat Centre looking for local, hand-made crafts.

Perched on a rock behind a fenced pasture stood Norman, a goat with huge ringed horns that swept high upon his head and curved toward his back in elaborate spirals. His beard was long and soft. He stood twice as large as domesticated Pierre and the infamous Buck Buck.

When I laid eyes on Norman, I thought of every fairytale, folktale, and epic story that I have ever read. Norman was a living version of Narnia’s Mr. Tumnus. I was smitten.

Well accustomed to sticking my fingers into the mouths of milk hungry calves, my initial reaction to greeting Norman was to offer my fingers in peace. He flipped his lips and licked my fingers. He and his field mate Sherman smelled of the best goat cheese you have ever eaten.

Notes of warm, late-September fields, autumn heather, mown hay, and rutting season wafted into your nasal passages, and into your memory. Norman and Sherman smelled of Ireland’s ancient past.

Recently, I have had the pleasure of sharing emails with Sinead Keane, Director of Marketing & Communication, resident researcher at the Old Irish Goat Centre, and self-proclaimed “Goat-Obsessive.”

If you plan a visit with the goats at the Old Irish Goat Centre in Mulranny, County Mayo, you will readily fall in love with these truly special creatures.

Dating back 5,000 years, the Old Irish Goat would roam in feral herds led by the females. Interestingly, some male goats would form “bachelor” herds. While the male goats bear the long beard and impressive horns, the females are a bit more delicate in frame. Both, however, possess ancient adaptations which allow them to survive the remote and rugged Irish terrain.

Herd survival was taught to the young goats through tests in which they would run and hide, a goat form of hide and go seek with the same peer pressure found in playground games. Much like young humans, not everyone is fast and athletic, some of us may fall behind the race, relying on our intellect for survival; and so, the slower goats would use a bit of trickery: hiding and looking for more efficient paths to keep up with their more athletic peers.

Otherwise, the young goats would risk being ostracized by the herd, and survival would be at stake.

The Old Irish Goat is present in the annals of Ireland’s history. In years past, Dublin foundlings or orphans, would be brought to the Wicklow Mountains and the more accommodating female goats would act as a wet nurse, providing the motherless infant with nutrient-dense milk. Strange, but true.

The Book of Kells

Illuminations of the Old Irish Goat date back to the ancient Book of Kells and the Book of Armagh. Carved drawings of the goat have been discovered in Megalithic tombs dating to the Celts and the Vikings.

Goat skin was used by the monks for parchment and even covered the frame of the Bodhrán, Ireland’s traditional, hand-held drum. Archaeologists have excavated artifacts of the side-blow horn made from the Irish goat horn.

In literature, the goat is found in poetry and prose. In James Joyce’s Ulysses, the goat roams among the gorse and heather of Howth foraging while Leopold and Molly Bloom share an amorous moment. Old time crooners remind us all, “Birds do it, bees do it, even educated fleas do it.” For generations, humans have looked to our natural world for survival, as well as inspiration.

Unfortunately, over the course of time, the Old Irish Goat fell to the travesties of human choice. Sport killing of goat herds, crossbreeding with modern, domesticated goats, and changes in farming practices led to the slow decimation of the Irish Goat, until it was believed that the Old Irish Goat was lost, living only in myth and legend.

The Images above are courtesy of Sinead Keane

Marketing & Communications

The Old Irish Goat Centre

Mulranny, Co. Mayo

Photo credit:

Image 3 & 4: Richy Needham

Image 1, 2, 5: Des Mullan

Old Irish Goat Society

Organized in the Burren, County Clare, the original Old Irish Goat Society was formed in 2006. Lacking necessary support, the group disbanded and later reconvened in 2012 in Mulranny, County Mayo, Ireland.

Observations of curious-looking feral goats were noted. Ray Werner, a primitive goat expert based in London, flew to the west of Ireland and joined fellow researchers. Three goats were caught, and DNA was obtained. Clinical proof established that the goats were descended from a pure herd that belonged to the ancient breed assumed lost.

In 2013, the mission of the Goat Society was actualized, and the sanctuary opened in Mulranny. A breeding program was established to ensure that one of the most unique and ancient symbols of Ireland’s remarkable heritage would be preserved for future generations.

Research continues into the past and future promise of the Old Irish Goat. The goats are doing what they do best: foraging on invasive gorse and heather, helping the environment and farmers with conservation grazing, a natural and sustainable form of land management.

While there is no exact count of the population of goats roaming the mountains of Ireland, we are assured of the authenticity of their species. Though elusive, wild goats can be spotted across Ireland.

Old Irish Goats and rabbits co-exist on the uninhabited Dalkey (Goat) Island located in the county of Dún Laoghaire-Rathdown, while colonies of seals swim among the waters of the Irish Sea.

Considered endangered, the Old Irish Goat is not protected by the state. Teams of dedicated citizen volunteers work to raise awareness of the importance of protecting this species. Thanks to the dedicated non-profit groups, researchers, conservationists, scientists, historians, and self-professed “goat obsessives,” the Old Irish Goat will continue to stand as a symbol of Ireland’s ancient heritage.

There is indeed promise for our future when the birds and beasts of nature are allowed to live as nature intended.

Connect with the Old Irish Goat at [email protected] or in person at the Old Irish Goat Visitor Centre and Craft Shop – Mulranny, Co. Mayo, Ireland.