And there I was in the middle of a field . . . The windings had been ploughed, furrows turned . . . Within that boundary now Step the fleshy earth and follow The long healed footprints of one who arrived From nowhere, unfamiliar and de-mobbed, In buttoned khaki and buffed army boots, Bruising the turned-up acres of our back field To stumble from the windings’ magic ring And take me by a hand to lead me back Through the same old gate into the yard Where everyone has suddenly appeared, All standing waiting. - (An excerpt from “In a Field” by Seamus Heaney)

My father was nine years old when the United States entered World War II. He and his friends created a club called the Beaver Chiefs. Their mothers volunteered with the Red Cross and the boys dedicated their time to patriotism and mischief, albeit in equal parts.

Roaming the streets of their Chicago neighborhood, the Chiefs searched for discarded scrap metal and bits of rubber from worn out tires. They weeded their neighbors’ Victory Gardens and lifted half-smoked cigarettes from the sidewalk.

The Beaver Chiefs met in the basement of an old brownstone apartment building to share war stories, bubblegum, used cigarette butts, comic books, and tall tales, until the resident hermit chased them out one day.

I grew up listening to Big Band music with my dad. He and I both love the Andrew Sisters and their rendition of “Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy.” On cold winter nights, Dad and I have boogie-woogie dance parties where he and I shuffle to our favorite tunes. We reminisce about old-time movies and talk about how different life is now.

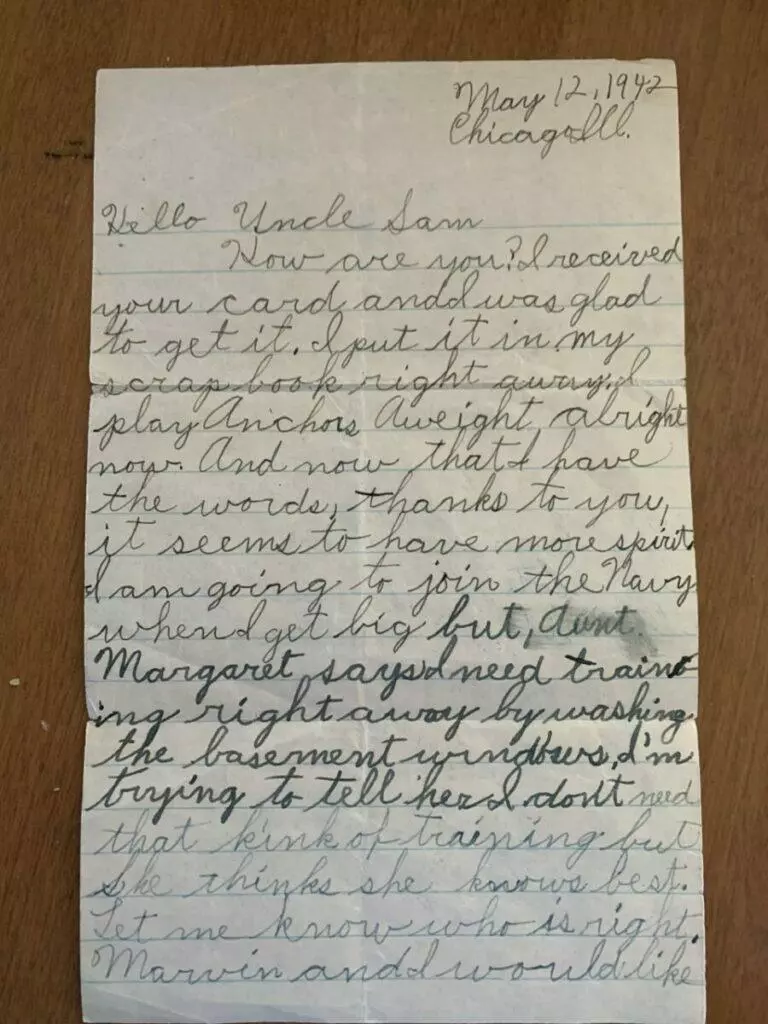

Recently, my dad shared with me a childhood letter that he wrote to his Uncle Sam, who served in the United States Navy during World War II. My dad told Uncle Sam how he was learning to play “Anchors Aweigh” on the accordion, and that when he was grown, he was going to join the Navy. My father’s Aunt Margaret told my dad that “he needed to start training right away by washing the basement windows.”

My dad looked at the war with innocence and wide-eyed respect for the soldiers who fought. Little did he imagine that one day he would marry a girl whose two brothers served in World War II, one fighting in the Battle of the Bulge; and that both men would return home safely to the Missouri farm where they were born and bred.

The Korean War

As he was a boy during WWII, the cold realization of wartime did not truly resonate with my dad until he was drafted for the Korean War. He explained that during basic training it dawned on him that he could be fighting on the frontline, and all the wistful tunes and romantic films from his youth could not erase the fear that he felt. But like the men and women before him, my father was ready to serve no matter the cost.

Recently, I asked him if he was ever aware of the terror of the unknown during WWII. Did he ever think that his Chicago neighborhood would be bombed during the night? Fortunately, as a boy, he never experienced that intense fear, but despite his youthful age he did his part to keep the neighborhood safe.

When my dad turned ten, he worked as a messenger boy for the local air raid warden. The warden conducted weekly checks ensuring that all the lights in the bungalows and brownstones were out after sunset. It was my Dad’s responsibility to run to the neighborhood ward office to report that the houses were dark, and conditions were safe.

Victory Day

On May 8, 1945, Victory in Europe Day, my father distinctly remembers going on the streetcar with his mother to the celebrations in downtown Chicago. At that time, every neighborhood revolved around a Catholic parish, and all the bells across every neighborhood were ringing with joy and relief. At ninety-years of age, my dad can still hear the bells ring.

Tales of innocence and experience, fact and fiction sometimes merge in the telling of a story until it is difficult to distinguish where one narrative thread ends, and one begins. In truth, I have listened to the stories of elderly men and women, absorbing the treasured memories that they have shared. While I am a keeper of tales, I like to think that I give new life to their memories through my writings, and their stories will live on for future generations.

My father-in-law died suddenly at the age of sixty-eight. As my father can hear the bells from VE Day, I can hear my father-in-law’s words: his wisdom and wit.

I first traveled to Ireland with my husband before we were engaged. My father-in-law showed me the vast hedges of rhododendron that lined the road to his Achill Island. He brought me to Slievemore and pointed out the ridges in the mountainside where potatoes were once sown.

Keem Beach

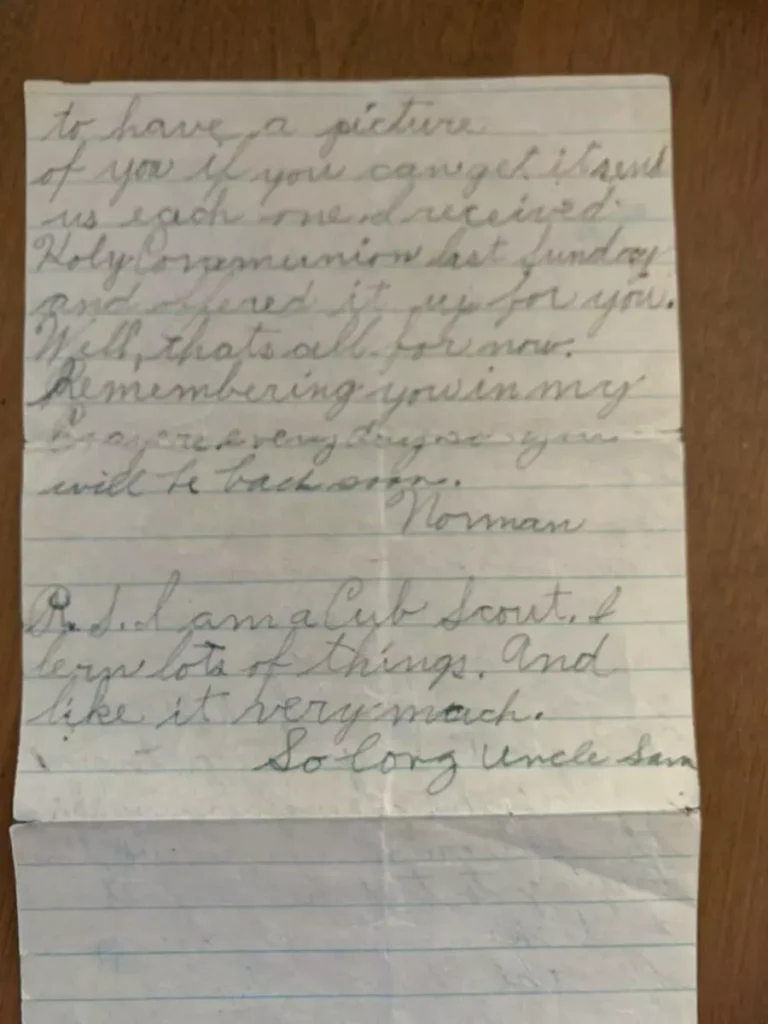

Proudly, he brought me over the rugged mountains that led to Keem Beach. He pointed out the WWII lookout spot atop the cliffs of Croaghaun upon Moyteoge Head and explained how a man from the village made the walk each day to the shelter to keep watch for German U-Boats. We half joked that by the time the sentry made his way back down and over the mountain, the entire island would have been invaded.

Irony aside, from September 1939 to June 1945, eighty-three Lookout Posts (LOPs) were established and monitored by members of the Local Defence Force all around the coasts of Ireland. The mission was to protect the neutrality of Ireland as well as to guide Allied pilots as they flew over the island. Eire and the post number was written in white and visible from the neutral air space.

Last summer we visited another WWII Lookout Post, located atop the stunning cliffs of Downpatrick Head, County Mayo. While our son and daughter were taking daring selfies high above the soft meadowed fields that yield to cliffs which rise one hundred and fifty feet above the crashing Atlantic waves, my husband and I remained on safer ground exploring the history behind Eire 64. Unlike the ruins of the post above Keem Bay, Lookout 64 is marked with placards that detail the interesting history behind this windswept post. Songs and stories, poems and plays have been written about the struggle of war. Words act as shelter for memory; lines of verse illuminate the faceless men and women who compose our shared histories.

In a Field

Two months before he died, Seamus Heaney’s last known poem entitled “In a Field” was published in The Guardian. Heaney writes of a WWI soldier who attempts to make his way home and is discovered by a child. The poem is an homage to endings and beginnings, the parallel truths of the walls and boundaries that isolate humanity. Heaney writes of the human narrative that meanders over fields and strands, marking time for future generations.

*Susan holds a Master’s Degree in English from John Carroll University and a Master’s Degree in Education from Baldwin-Wallace University. She may be contacted at [email protected]