Akron Irish: Witness

By Lisa O’Rourke

Being a witness is a curious thing. It means more than just seeing.

It coils around an experience and wraps its tail around the conscience. Being a witness implies presence and that compels thought at the least, and perhaps invokes action. Witnesses often don’t know that they are until well after the event. History names them.

And so it was with Francis Browne. If you know the name at all, you know him as Fr. Browne.

And if you do know his name, it is because he bore witness to one of the greatest tragedies of the 20th century, the Titanic.

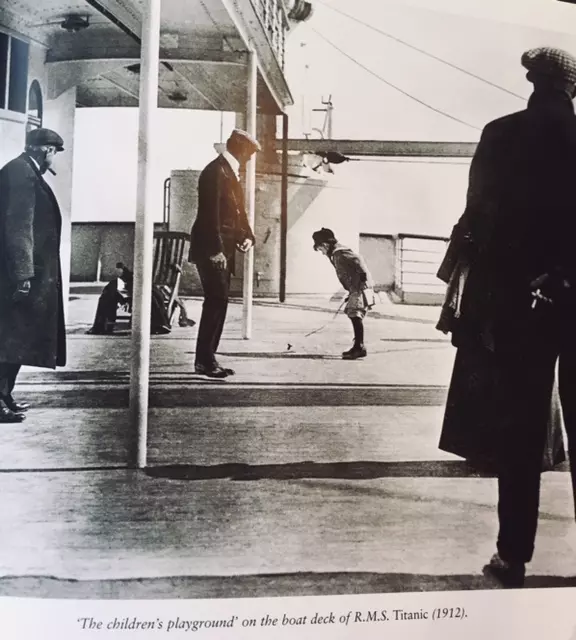

Browne was an amateur photographer who happened to receive both a camera and a ticket on the maiden voyage of the Titanic from his uncle. Cameras were rare enough at that time and those lucky enough to have one, used them. The camera captured his imagination.

The hold that photography had on him had to be due, in part, to his early experience with it. He set sail, going from Southampton to Cherbourg and then on to Cobh. He charmed a couple that wanted to pay for him to continue on to New York with them.

Get Off That Ship

He missed the last leg of the voyage due to an admonishment from a superior to GET OFF THAT SHIP. We all know what that kind of message means when you receive it in print, and that stern telegraph surely saved his life.

Fr. Browne’s photographic eye was naturalistic. His photos capture the common people on the boat, those anonymous souls sailing third class, along with some candid shots of the beleaguered captain, Edward J. Smith and the other crew members. The photos have a wistful quality, contrasting the hubris of being part of what was an amazing opportunity with what we know eventually was a horrifying catastrophe.

Francis Browne was born in Cork in 1880. He was orphaned before he was ten years old and sent to live with the aforementioned generous uncle, the Bishop of Cloyne, Robert Browne.

Francis, in turn, became a priest, joining the Jesuits as a young man. He was not long ordained when he joined the ranks as a chaplain to the Irish Guards in World War I.

The Bravest Man I Ever Met

He was wounded and exposed to mustard gas several times, participating in some of the most horrific battles of the war including Flanders and the Somme. He was awarded both the British Military Cross and the French Croix de Guerre, while being called the “bravest man I ever met” by an English commander.

The war did take a toll on his health after the fact. Time in the trenches and exposure to mustard gas left him in need of a warmer climate to recuperate. He travelled for a few years, journeying to such exotic locations as South Africa, Australia and Sri Lanka, camera in hand.

Upon his return, the Jesuits assigned him to be a local missionary, which meant that he traveled around Ireland, Scotland and Wales for over thirty years. He passed away in 1960, his primary legacy being that of a beloved priest.

Whether he viewed himself as an artist is unknown. He had a passion for photography, but he did not publicize his photographs, except to sell some of them to news outlets after the sinking of the Titanic. The artists that he knew in life, were literary ones.

His academic career introduced him to James Joyce; they attended university together. Joyce had a character named Fr. Browne in Finnegan’s Wake. Father Browne was also a friend of Rudyard Kipling, whom he met during World War I while Kipling’s son was in the Irish Guards. The fact that Fr. Browne kept all of his negatives is one assertion that he believed that they had some value, artistic or not.

Photograph Witness to History

It was well after his death, in 1985, that a fellow Jesuit found a treasure trove of images. Well over twenty-five books have been published from his thousands of restored negatives. Probably his most famous photos are ones from his early days, those being images from the Titanic and the trenches of World War I.

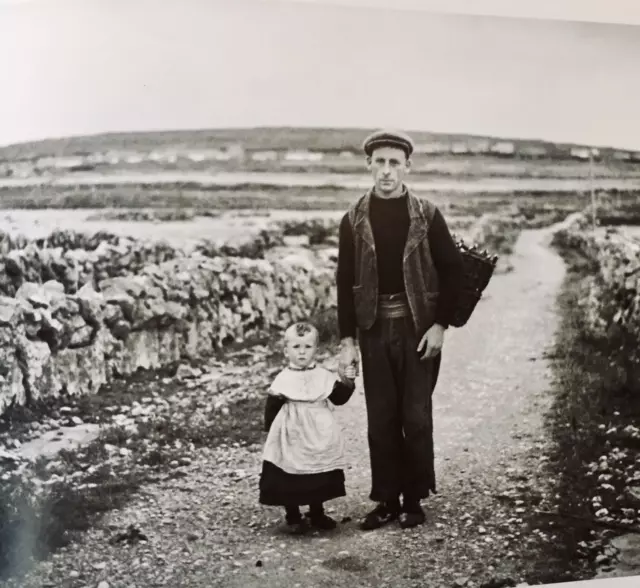

Fr. Browne’s pictures are unposed, capturing people in their everyday activities. His eye for composition is excellent, contrasting dark and light and different types of images. His humanity, compassion toward the lives of common people, and curiosity shine through these photos.

Browne’s style remains relevant and contemporary long after his passing. His images make history singular and alive, honoring the anonymous individuals he captured.

One of the most powerful ways to bear witness is through images. Photographs have the power to move us, they have an immediacy, a sense that there is no interpreter between subject and audience.

Being a witness is a curious thing. We need look no further than our own backyards to see that. We are witnessing our own history on so many fronts. There have been so many images for us to lock on to, so many containing an element of sadness, of hardship.

A friend of mine once told a story about three dogs chasing a rabbit. Two of the dogs eventually dropped from the chase but one persisted. When the owner was asked why the last dog kept up his pursuit, the owner said that dog was the one that saw the rabbit. These times call for us to see and pursue the rabbits that we do see, and try to understand that others may be seeing something that we missed.

O’Donnell, E.E., (2007) All Our Yesterdays: Father Browne’s Photographs of Children and their favourite poems. Currach Press.

*Lisa O’Rourke is an educator from Akron. She has a BA in English and a Master’s in Reading/Elementary Education. Lisa is a student of everything Irish, primarily Gaeilge. She runs a Gaeilge study group at the AOH/Mark Heffernan Division. She is married to Dónal and has two sons, Danny and Liam. Lisa enjoys art, reading, music, and travel. She likes spending time with her dog, cats and fish. Lisa can be contacted at [email protected].

Please send any Akron events to Lisa’s email!