Akron Irish: Be Quiet

By Lisa O’Rourke

As longtime students of the Irish language, my fellow language friends and I were over the moon to hear that there was a new movie that was in Irish. We no sooner absorbed that news when we heard that it was the first Irish language film to be nominated for an Oscar as a foreign film.

There have been several Irish language features over the last few years. I would classify these films as gritty, famine-revenge-porn type of things, think “Braveheart.”

I would not dismiss them; they did have historical merit and stories that needed to be told. What was a little tough to take was that the Irish language was once again painted in the patina of poverty and suffering, the coating which has plenty to do with the stigma it still carries.

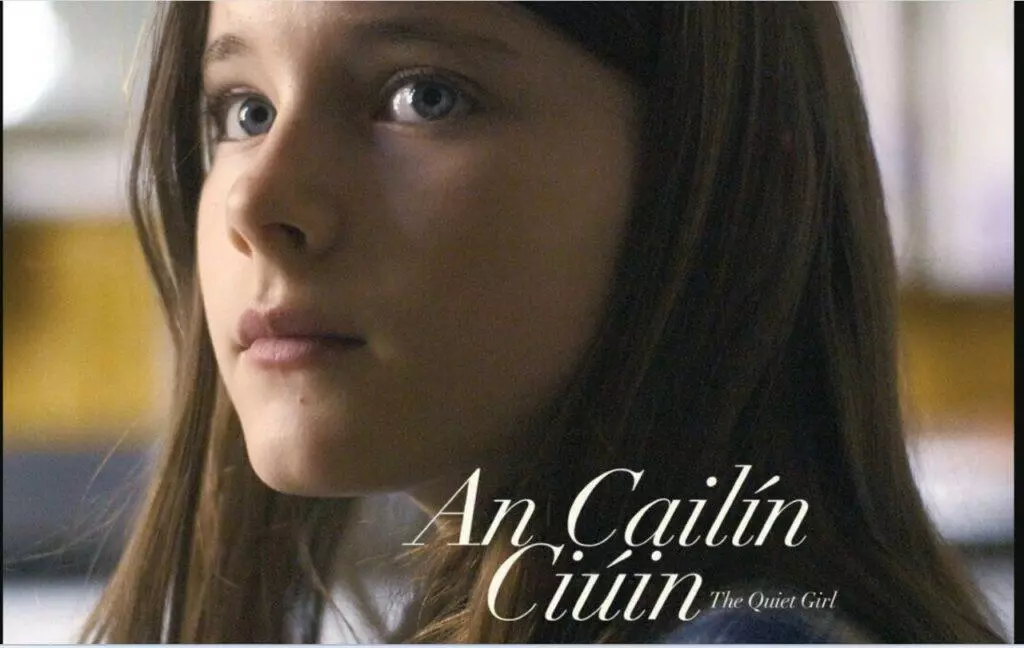

An Cailín Ciuin

Then the foreign film categorization was a bit of a head-scratcher, but that has to be because of the language, since plenty of Irish films are nominated alongside ones from the US or UK. The title was in Irish too, originally distributed as “An Cailín Ciuin” (Un Kawleen Kuwin) and now as “The Quiet Girl.”

Set in 1981 Waterford, this Ireland looks foreign, and would look that way to many Irish, especially the younger set. It was a different world, a different Ireland, a country that knew poverty and the web of snares it sets for people.

It is hard not to think of the iconic “Quiet Man” too. Despite the quiet, the two Irelands are very different places. While a gentleness runs deep in both, the girl’s world is without much of the man’s lightheartedness.

The film opens to a field, with long hay blowing under a moody gray sky. Female voices are calling someone home, over a breeze, far away. The camera moves to reveal a young girl, Cáit, unresponsive to the calls, lying buried in the grass.

And buried she is, unseen at home and school, a seeming non-entity, unless she is being perceived as slightly difficult, weird or wandering. While she is the focus of no one, it is her focus that is the eye of the film.

The movie is a series of cuts between what her eye is drawn to and her response to the world. Her eyes flicker almost imperceptibly, but the whole film is so quiet, those flickers are riveting and all-telling.

Pre-Celtic Tiger

Her Waterford home is decidedly pre-Celtic Tiger Ireland, it looks more like the 1960s. The dull grind of rural poverty is visceral in the scenes at Cáit’s home. Her pregnant-again shell of a mother is seen reading a letter amidst crying and shabby furnishings. We next see Cáit with her suitcase, leaving her gray barren yard of a home, with no goodbyes on either end.

iIrish recommended Posts:

- This Just In: MICHIGAN IRISH AMERICAN HALL OF FAME NAMES 2024 MEMBERS

- This Just In: Pittsburgh Day of Irish Entertainment is Coming

- This Just In: A week is still a long time in politics

- This Just In: Recognition of Palestinian Statehood an important step for the Palestinian people – Mary Lou McDonald TD

- This Just In: Update on Bringing National Women’s Soccer League to Cleveland

Staring out the window of the car driven by her lout of a father, we see the clouds moving lazily across the sky, the weather brightening as they go. Down a dappled lane of ancient oaks, Cáit lands at the Kinsella’s, her mother’s sister Eibhlín and her husband Seán. You see the pity in Eibhlín’s eyes as she absorbs the feral neglected child.

Cáit’s family have sent her to live with them for the summer. It could seem a bit over the top, but the movie really captures a time and place.

As soon as the setting changes, everything else changes for Cáit. She sees, with a lyrical touch, the dew on the grass, the light in the trees, the reflections in water, the beauty in nature’s granular detail. The movie does what art is supposed to do, elevate the ordinary to the sublime.

The clichéd stock Irish characters appear, and they feel more like truth. There is the mother, whom poverty and all that goes with it has ground down to a sad shadow of a person. There is the old Irish sexism in parts, especially in evidence in the foggy, drunk, slightly menacing father.

You can see the icy fragile hearts of the nurturing aunt and uncle preparing to melt like they were out in the sun. This feels different than stock cliché though; the three main characters all have a deep well of stoicism.

Cáit and the Kinsellas accept what life hands them with quiet reserve. The story moves them along until they can open their respective heart fortresses to love.

There are a few comedic scenes too, with the Kinsella’s neighbors. One has a donkey laugh that is funny just to hear. The other is a nosy neighbor who is comically awful. She is walking proof that the Irish suffer from envy as surely as anyone.

The use of Irish in the film parallels the use of light. Scenes of dull unhappiness are cool and gray, and the language is English. In the warm sunlit farm of Seán and Eibhlín Kinsella, the language is Irish. Spoken in soft hushed tones, liberally peppered with pet names like a stór (my treasure), it is the language of love in this movie.

If you are in doubt, look and see if the dodgy characters in the film speak a word of Irish. The Irish language is often accused of sounding harsh and guttural, but the scenes in this film show another side of it.

Along with the Irish, much of the movie is so quiet and still, it feels like nothing happens, like watching a flower bloom. And like that flower, it is a beautiful and emotional thing to watch.

It is a funny thing that people who are known for loving language and being some of the most loquacious people on earth have a reverence for quiet. Maybe that is the reason for it. There is an old proverb that says, “Many a man’s tongue has broken his nose.” I love that quote.

It is a tribute to the slightly taciturn stoicism that we attribute to many rural people, the Irish in particular. Silence, not that I have any talent for it, is a choice. Seán has a wonderful quote in the film that mirrors the proverb, “Many a person missed the chance of saying nothing and are the worse for it.”

*Lisa O’Rourke is an educator from Akron with a BA in English and a Master’s in Reading/Elementary Education. She is a student of everything Irish, primarily Gaeilge, and runs a Gaeilge study group at the AOH/Mark Heffernan Division. She is married to Dónal and has two sons, Danny and Liam. Lisa enjoys art, reading, music, and travel. She enjoys spending time with her dog, cats and fish. She can be contacted at [email protected].

Please send any Akron events to be published in iIrish to my email (or Click Here: [email protected])!