Speak Irish: The Blind Man’s Vision

- John O'Brien

- June 28, 2023

- Edited 6 months ago

Table of Contents

By Bob Carney

June 28, 2023

I’ve been relistening to a series of lectures by Professor Marc C. Conner from Washington and Lee University, collectively titled “The Irish Identity, Independence, History and Literature.”

They were originally distributed to coincide with the 2016 anniversary of The Rising.

The Irish Renaissance

It’s no secret that Ireland has produced some of the world’s best writers, poets and playwrights. Yeats, Shaw, Joyce, Wilde, Lady Gregory, Synge and many others found their voice writing in English about Ireland, it’s people and culture in what we call the Celtic Revival. A literary component of the Irish Renaissance.

It was an interesting concept of taking ancient celtic and Irish motiffs and uniting a troubled land and it’s people. It eliminated, for the most part, differences in politics and because the stories were pre-Christian, religion, allowing the Irish to become one people and take pride in themselves and their culture.

An Gorta Mór

Regrettably, many writers at the time had to make a choice to write in English or Irish. Your audience would be smaller if you chose to write exclusively in Irish. After An Gorta Mór, the Great Hunger, the number of Irish speakers fell dramatically.

In 1843, Irish was the main language of around three million people in Ireland, but, fifty years later, due to the loss of life and emigration, only 680,000 remained that could speak the language. Many of the Irish speakers from that era were simple working people, some could not read, and others lacked the time or resources to read.

Yeats and Lady Gregory

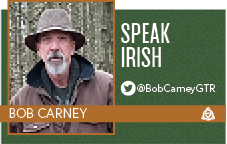

We did have many great writers that did choose to write in the language of their people, rather than the language of “the strangers.” Lady Gregory not only learned Irish, but wrote extensively in the language, capturing the tales she was told from those she met in the West.

Her knowledge benefited Yeats in his poetry. When Yeats was approached about writing a compilation of Irish mythology, he declined, but Lady Gregory took on the task and wrote two volumes, “Cuchulain of Muirthemne” and “Gods and Fighting Men.”

Yeats himself called these books the greatest to come out of Ireland. These were written in English that was closest to the Irish spoken in Ireland for the last few centuries.

Lady Gregory

Conradh na Gaeilge and Hyde and Pearse

Douglass Hyde and Patrick Pearse also wrote in Irish. Hyde formed Conradh na Gaeilge, or ,The Gaelic League, an organization that is dedicated to preserving the Irish language and through that, Irish culture and traditional arts. Hyde also became president in 1938 and serve until 194, but never intended for Conradh na Gaeilge to be a political institution.

Douglas Hyde

Pearse, a school teacher, became very active in Conradh na Gaeilge. In 1913 he wrote this about it: “We had one and all of us (at least, I had, and I hope that all you had) an ulterior motive in joining the Gaelic League. We never meant to be Gaelic Leaguers and nothing more than Gaelic Leaguers. We meant to do something for Ireland, each in his own way. Our Gaelic League time was to be our tutelage: we had first to learn to know Ireland, to read the lineaments of her face, to understand the accents of her voice; to repossess ourselves, disinherited as we were, of her spirit and her mind, re-enter into our mystical birthright. For this we went to school to the Gaelic League. It was a good school, and we love its name and will champion its fame throughout all the days of our later fighting and striving. But we do not propose to remain schoolboys for ever.” From, “The Coming Revolution.”.

The Blasket Contribution

Later, writers from the Blasket Islands shared stories of life and death on these remote islands in Irish, with an eloquence usually found in the writings of the highly educated. Tómas Ó’Criomthain’s, “The Islandman,” told the story of his life there. Maurice Ó’Sullivan’s, “Fiche Blian ag Fas,” or “Twenty Years A’Growin” is one of my favorite books about island life.

Peig Sayers, a seanchaí of the old oral tradition, encouraged scholars to come to the Blaskets to visit her. Robin Flower became a good friend visiting often. Peig was unable to write, but another young scholar,Kenneth Jackson, recorded her stories, and in 1938, published “Scealta on mBlascaod “Stories From The Blasket.” Her son, Mike File, collected more of her stories for a second book, titled, “An Old Woman’s Reflections”.

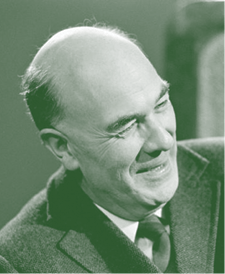

Máirtin Ó Diréan

Space, does not allow me to share more of the writers that Ireland produced, and admittedly, I discover more almost weekly. The poetry of Máirtin Ó Diréan was one such recent discovery.

Máirtin was born in 1910 on Inis Mór. At the age of eighteen he left the island and joined the Post Office in Galway. He became very involved in the Irish language movement.

He became secretary of the Galway branch of the Gaelic League while employed there. In July of 1937, he moved to Dublin, where he worked as a clerical officer and later, in the Dept. of Education.

In Dublin, he attended a lecture by the poet and gaelic scholar, Tadhg Ó Donnchadha. He was inspired to write poetry himself in the language he was raised with. His books, collections of his poetry, introduced a new generation and a new voice to modern Irish language poetry in Ireland. Máirtin continued writing until his passing in 1988, including a series of essays about his early life on the Aran Islands.

Below is an excerpt from his poem, “Fís an Daill,” or “The Blind Man’s Vision.” It is the story of an old blind seanchaí who attempts to tell the crowd in what is presumably a pub, about the ships he sees on the western ocean and the people on board enjoying their voyage.

There is a beautiful rendition on YouTube that is very accessible for learners of Irish of all levels. It is recited very slowly and clearly, and is very easy to follow.

Hearing the language is still one of the best ways to help us with our own pronunciation. I hope you enjoy it and are inspired to explore more of the great writers Ireland and the Irish language have and continue to give us.

“Is dúirt duine amháin Nach raibh ann ach dall

Is nach raibh ina chaint ach rámhaillí ard

Is choaic mé gné

An tseanchaí léith

Is í ar lasadh ag fí na háillie

Is d’eirigh mé faoi fheirg Gur fhág mé an áit Is gur dhúras nárbh eisean

Ach iadsan a bí dall.”

“One of them called him a blind old fool

And his story nothing but rambling talk.

But still the face of the blind seanchaí

Was lit by his beautiful vision

So I stood up, now seething,

Stalked out of the place

Saying it’s not him,

But them who are blind.”

- This Just In: MICHIGAN IRISH AMERICAN HALL OF FAME NAMES 2024 MEMBERS

- This Just In: Pittsburgh Day of Irish Entertainment is Coming

- This Just In: A week is still a long time in politics

- This Just In: Recognition of Palestinian Statehood an important step for the Palestinian people – Mary Lou McDonald TD

- This Just In: Update on Bringing National Women’s Soccer League to Cleveland

*Bob Carney is a student of Irish language and history and teaches the Speak Irish Cleveland class held every Tuesday at PJ McIntyre’s. He is also active in the Irish Wolfhound and Irish dogs organizations in and around Cleveland. Wife Mary, hounds Rían, Aisling and Draoi and terrier Doolin keep the house jumping. He can be reached at [email protected]