Illuminations: The Glimmer Man

Illuminations: The Glimmer Man

By: J. Michael Finn

Ireland remained neutral during World War II. From 1939 until 1945 the war years were referred to in Ireland as The Emergency, or Ré na Práinne in Irish (pron: ree na prahn). The war years proved significantly challenging for the Irish, but like most periods of crisis, the Irish found various ways of coping.

Months before the war began, on February 19, 1939, and with broad public support behind him, Taoiseach Éamon de Valera announced the 26-county portion of Ireland, known officially as Éire (pron: air-ah), would be neutral if war broke out.

The United Kingdom declared war on Germany on September 3, 1939, just two days after Germany had invaded Poland. De Valera spoke again to the Irish people on the same day, reaffirming Ireland’s policy of “friendly neutrality.” He said that neutrality was to be kept “by addressing ourselves to the practical questions that we do not want to get involved in this war, and we merely want to keep our people safe from such consequences as would be involved by being in the war.”

The Emergency was proclaimed by Dáil Éireann on September 2, 1939, allowing the passage of the Emergency Powers Act of 1939 the following day. This gave sweeping powers to the government, including internment, censorship of the press and private correspondence, and control of the economy. The war years were known as The Emergency because of the wording of the constitutional article employed to suspend normal government of the country.

Irish neutrality presented a real national emergency. The country was dependent on Britain for just about every commodity from coal and oil to tea and candles. Strategies had to be developed for the acquisition and transportation of necessary commodities. In addition, a process for rationing many items had to be developed.

Fortunately, de Valera wisely appointed the “practical and pragmatic” Sean F. Lemass as Minister for Supplies. Ireland had to achieve an unprecedented degree of self-sufficiency and it was his difficult task to organize what little resources existed.

In 1941, he established the Irish Shipping Limited, Ireland’s first merchant marine operation, to keep vital supplies coming into the country. A variety of ships were acquired. Most of the ships were used and were purchased from a variety of countries, including America; a few had been abandoned by their owners; and most were in need of repair.

Due to Ireland’s neutrality, Irish merchant ships were not permitted to travel in convoys across the Atlantic to avoid German U-Boats. Despite being well marked (tricolors and ‘EIRE’ were painted in large letters on the ship’s sides and floodlighting at night), sixteen Irish merchant ships were sunk; 149 merchant sailors were killed and thirty-two wounded due to belligerent action. On November 16, 1942, thirty-three deaths occurred aboard the SS Irish Pine when it was torpedoed in the North Atlantic, south of Cape Breton Island, Canada, with the loss of its entire crew.

Coal and Gas

On the home front, Ireland also encountered shortages of coal and gas. While Ireland had a few coal mines, they did not produce the quantity needed for the entire country. The city of Dublin alone required over 750,000 tons of coal each day.

Various attempts were made to utilize Irish turf to replace coal. Turf was not a good replacement as it generated considerably less heat than coal, so more tonnage of turf was required to produce the same amount of heat.

In its natural state, turf is 95% water and must be thoroughly dried before it will burn. Despite its drawbacks as a source of heat, turf was harvested at a frantic rate during the war. The main avenue of the Phoenix Park was eventually flanked on both sides by ton upon ton of turf destined for the fires of the people of Dublin.

The avenue was soon christened The New Bog Road. The use of turf as a fuel source during The Emergency reinforced the government’s commitment to develop Ireland’s bogs as an indigenous source of energy.

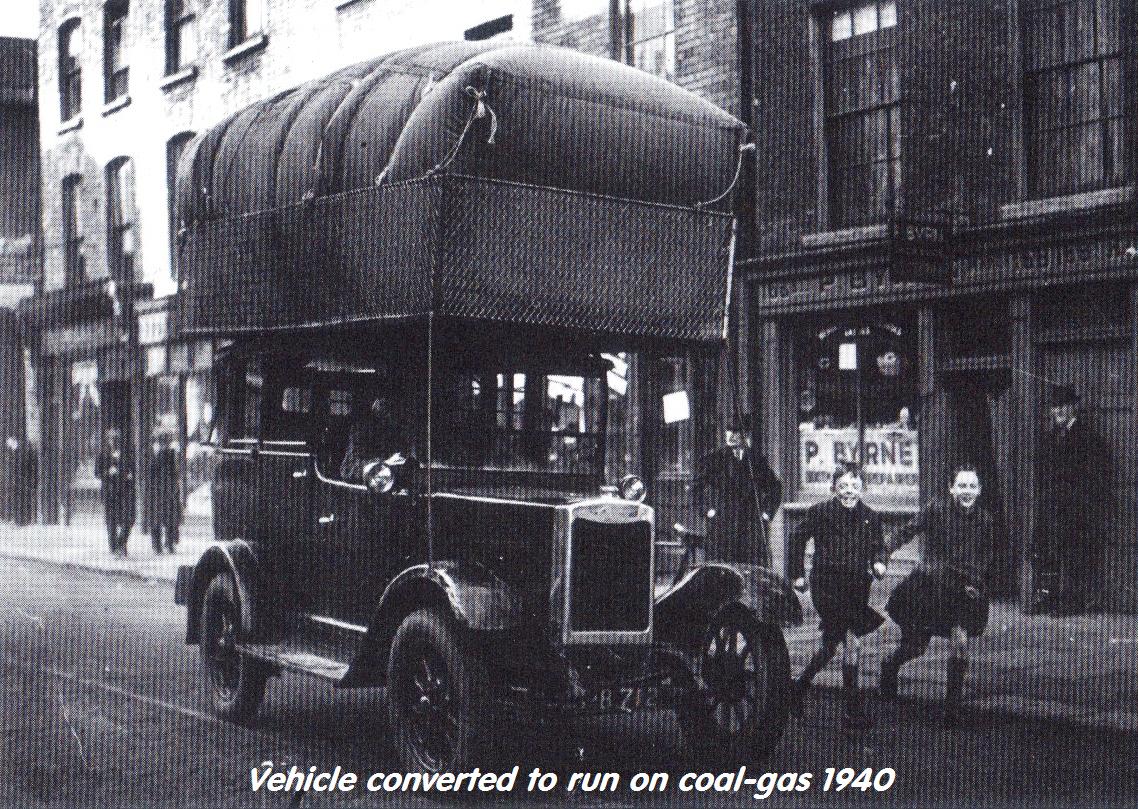

Coal-gas is a flammable gaseous fuel made from coal and supplied to the user via a piped distribution system. Due to the coal shortage, it also was in short supply. It was known in Ireland as town-gas, and was used for cooking, to provide street lighting, and was also used for lighting in homes.

Because gas (i.e., petrol) for vehicles was in short supply, private vehicles were often converted to run on town-gas by using a large, rubberized bag that held the town-gas supply and was attached to the top of the car. This practice ended later in the war, when only essential vehicles were allowed to be on the roads, causing many to revert to bicycles and horse drawn carriages to get around.

The Glimmer Man

In order to ration the limited supply of town-gas, its use was confined to certain times of the day. Town-gas could only be used during two periods of the day. Dubliners soon discovered that a “glimmer” of gas remained in the pipes after the supply had been cut off and that this could be used to heat a can of soup, boil water for a pot of tea or warm a baby’s bottle. A children’s rhyme of the time went: “Keep it boiling on the glimmer, if you don’t, you get no dinner.” As a result of this glimmer of gas, a new profession was born – The Glimmer Man.

The dreaded Glimmer Man was an official employed by the gas company to snoop around, spying on the citizens who may be using the last glimmer of gas that remained in the pipes. The Glimmer Man had extraordinary powers: he could legally enter your house and check for recent illegal usage of gas. Guilty parties could be fined and have their gas disconnected (the term Glimmer Man is now applied to any perceived intrusion into individual privacy, especially of a bureaucratic nature).

The press was censored during war years as part of the Emergency Powers Act. They could not print anything about the war, about Irish citizens who had joined the British military, or any information that would favor one side of the conflict or the other.

Newspapers had to submit their daily copy to the censorship office, whose decision was final. Editors became skilled at disguising war news to avoid the censor’s pen.

Robert Smyllie, editor of the Irish Times, would list the cause of death for Irishmen killed in the war as “dying of lead poisoning.” A former reporter of the paper was aboard the RMS Prince of Wales when it was sunk by the Japanese somewhere off Singapore. Smyllie reported: “The many friends of Mr. John A. Robinson, who was involved in a recent boating accident, will be pleased to hear that he is alive and well.”

If you would like to read more regarding The Emergency, an excellent book is The Lost Years: The Emergency in Ireland 1939-1945, by Tony Gray, Little, Brown Book Group, U.K., 1998. It covers many more details regarding the period by someone who lived in Ireland during the war.

*J. Michael Finn is the Ohio State Historian for the Ancient Order of Hibernians and Division Historian for the Patrick Pearse Division in Columbus, Ohio. He is also Chairman of the Catholic Record Society for the Diocese of Columbus, Ohio. He writes on Irish and Irish-American history; Ohio history, and Ohio Catholic history. You may contact him at [email protected].

Monthly newsmagazine serving people of Irish descent from Cleveland to Clearwater. We cover the movers, shakers & music makers each and every month.

Since our 2006 inception, iIrish has donated more than $376,000 to local and national charities.

GET UPDATES ON THE SERIOUS & THE SHENANIGANS!