Illuminations: The Cuba Five

Illuminations: The Cuba Five

By: J. Michael Finn

“They hither came with confidence; they hither came in banishment.”

The Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) organized the Fenian Rising of 1867 as a rebellion against British rule in Ireland. Following the suppression of the Fenian newspaper Irish People in September 1865 by the British, disaffection among Irish nationalists grew. During the later part of 1866, IRB leader James Stephens raised funds in the United States for a fresh rising planned for the following year.

The Fenian Rising of 1867

Sadly, the Fenian Rising of 1867 proved to be a poorly organized affair. A brief rising took place in County Kerry in February, followed by an attempt to take the city of Dublin in early March. Due to the combined effect of weak planning and infiltration by British informers, the rebellion never got off the ground.

Most of the Fenian leaders in Ireland were arrested and imprisoned. The British penal system of that time was brutal under normal circumstances, and the Fenians suffered much harsher treatment than the regular inmates. One prisoner, Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa, consistently refused to conform to the strict prison environment and was singled out for solitary confinement and other harsher punishments.

The imprisonments were followed by a series of attacks in England aimed at freeing Fenian prisoners by force, including a bomb in London and an attack on a prison van in Manchester, for which three Fenians, known to history as the Manchester Martyrs, were executed on November 23, 1867. In 1869, a drive for an amnesty for Fenian prisoners gathered momentum. As a result of public pressure the British eventually declared a conditional amnesty for the Fenian prisoners. On January 5, 1871, they announced the release of thirty Fenian prisoners.

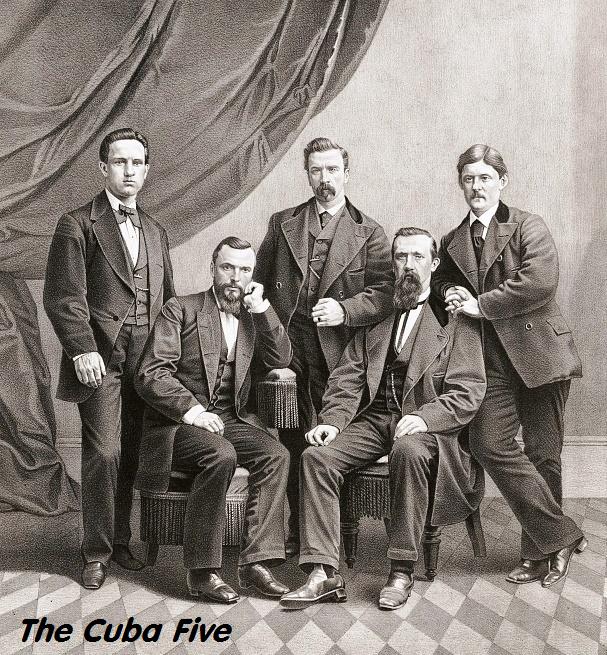

The British released the Fenians on condition that they exile themselves to the country of their choice and not return to Ireland until the term of their sentences had expired. Many chose to go to Australia, but five of the prisoners, John Devoy, Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa, John McClure, Henry Mulleda and Charles Underwood O’Connell chose to go to America.

The Cuba 5

The five Fenian prisoners were taken to the Liverpool docks under heavy police and army protection. There they boarded a steamship, the S.S. Cuba, bound for the United States. They would collectively become known as the Cuba Five.

On the cold evening of January 19, 1871, the S.S. Cuba drew within a few miles of landing at New York. Anticipation for their arrival was high among Irish citizens. It was decided that a delegation would meet the ship before it landed and escort the Fenians to port. Unfortunately, there were three groups who had the same idea.

The first group was aboard a US government cutter and led by Thomas Murphy, the revenue collector for the Port of New York. Murphy carried with him a letter from his boss, President Ulysses S. Grant, offering the five former prisoners the President’s regards and an official invitation to board the cutter for the last part of their journey.

Grant’s actions enraged the British. The Grant administration was anti-British due to British cooperation with the Confederacy during the Civil War. As one historian noted, “Twisting the lion’s tail was official Washington policy in Reconstruction America.”

The second boat included Democratic Party representatives from New York’s Tammany Hall, led by Judge Richard O’Gorman. The third boat contained a welcoming committee from the Knights of St. Patrick, one of the many Irish fraternal groups in New York. All three groups were determined to transport the exiles into New York Harbor.

The three boats raced toward the Cuba. The boat from the Knights of St. Patrick arrived first, followed quickly by the federal ship and lastly the Tammany Hall ship. The three groups met on deck and soon began to argue about who would be entitled the honor of escorting the five men to New York.

The Knights of St. Patrick argued they had arrived first; the US Government delegation argued that they were representing President Grant and outranked the other contenders; and the politicians from Tammany Hall argued that they were the official representatives of the City of New York.

The three committees met with the five Fenians aboard the Cuba. Pushing, shoving and general “trash-talk” ensued between the groups as the arguments continued. Accusations began to circulate that President Grant’s letter was a fake (it wasn’t) adding more fuel to the chaos.

A member of the US contingent insulted the Democrat group when he stated they wished to rescue the exiles “… from being made the tools of Tammany tricksters.” In response, the New York Health Commissioner, who was with the Tammany group, threatened to quarantine everyone on the ship unless the Fenians returned with the Tammany group. A brawl began among the greeters.

At midnight, after hours of negotiations, John Devoy asked that the five Fenians be allowed to confer before deciding who would escort them. The five Fenian exiles retired to a separate room to make their decision.

When they returned, O’Donovan Rossa read out a written statement signed by the five exiles. It read in part, “It is painful for us tonight, to see so much disunion among yourselves; and as you have not united harmoniously to receive us, we will not decide upon anything … we will remain on board tonight and we will go to a hotel tomorrow.” This news further enraged the groups and John Devoy scolded them that they if they could not act as gentlemen they should leave the vessel, which they all eventually did.

The Irish Brigade

The next morning, the Cuba landed at the Cunard docks, where the exiles received a grand welcome. They were transported to Sweeny’s Hotel in Manhattan, where they were they were welcomed by over 3,000 callers. The following day, they were paraded along Broadway, accompanied by the 69th Infantry Regiment (the ‘Irish Brigade’).

As the years went on, John Devoy, perhaps more than any other man, kept the struggle for Irish freedom alive among the Irish exiles in America, until his death in 1928. Patrick Pearse referred to Devoy as “the greatest Fenian of them all.”

Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa was as steadfast an enemy of English rule in Ireland as anyone who ever lived and would in death become the symbol for the 1916 Rebellion. Pearse would call him, “… this unrepentant Fenian.”

O’Connell, Muleda and McClure also continued to be involved in Fenian activity in the United States through the balance of their lives. With this article is a copy of a famous lithograph created by Robinson and Mooney depicting the Cuba Five. They are, from left to right: John Devoy, Charles Underwood O’Connell, Henry Mulleda, Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa and John McClure.

*J. Michael Finn is the Ohio State Historian for the Ancient Order of Hibernians and Division Historian for the Patrick Pearse Division in Columbus, Ohio. He is also Chairman of the Catholic Record Society for the Diocese of Columbus, Ohio. He writes on Irish and Irish-American history; Ohio history, and Ohio Catholic history. You may contact him at [email protected].

Monthly newsmagazine serving people of Irish descent from Cleveland to Clearwater. We cover the movers, shakers & music makers each and every month.

Since our 2006 inception, iIrish has donated more than $376,000 to local and national charities.

GET UPDATES ON THE SERIOUS & THE SHENANIGANS!