Cleveland Comhrá: The Irish Brigade

By Bob Carney

Forty-five years before the end of the American Civil War, an aging Thomas Jefferson had written a letter to a friend and said, “We have the wolf by the ears, and we can neither hold him nor safely let him go. Justice is in one scale, and self preservation in the other.”

Jefferson’s wolf was slavery, and it had been a point of dissension since the English arrived in America. The U.S. was concieved out of a revolutionary idea that Jefferson himself articulated in his Declaration of Independence, “All men are created equal and are entitled to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

It is no secret however, that Jefferson, Washington, Benjamin Franklin, Patrick Henry and many of our country’s founding fathers bought, kept, bred and sold human beings for financial gain. George Mason, John Rutledge and George Washington were three of America’s largest slaveholders. It should be noted that most of Washington’s slaves belonged to his wife Martha, they had belonged to her first husband. Washington and Jefferson harbored deep resevations about slavery in the future of America, but not enough to do anything about it even on their own plantations.

Was Slavery the Issue

Slavery was not the only issue to bring about the Civil War, an industrial revolution was taking place and a shift in financial power was happening, the Lousianna Purchase and westward expansion and the policies that would or might be enacted all played a role. But it was the debates between Lincoln and Stephen Douglas for a seat in the senate that pushed the divisive topic of slavery to the forefront.

Lincoln believed in preservation of the Union, non-extension of slavery and a strong federal government commited to a strong national economy. In response, Douglas played on the fears of many white Americans, painting Lincoln as a fanatic, an abolitionist who would have black men marrying white women.

Lincoln lost his bid for the senate, but became the 16th President of the United States in 1861. His goal was to keep the Union entact, but when Confederate batteries fired on Fort Sumter, forcing its surrender, he called on the states for 75,000 volunteers.

The Irish Broigade

Thousands of Irish and Irish American New Yorkers enlisted in the Union Army. Some joined regular regiments, but others formed three all Irish Volunteer Infantries, The 63rd New York Infantry from Stanten Island, and The 69th and 88th New York Infantry Regiments from the Bronx. These regiments formed the core of what is known as the Irish Brigade.

The Union Army felt that these regiments were a way to win Irish support for its cause. Most Irish immigrants lived in the North, but many were sympathetic to the South’s struggle for independence; it reminded them of their own fight against the British. Irish and Irish-Americans were not in a hurry to see slavery abolished; they saw it as a way to keep blacks out of the paid labor force and away from their jobs.

Union officials came up with ways to entice the Irish. They offered enlistment bonuses, extra rations, Catholic chaplains and more, to insure that the largest immigrant group in America would fight with the North. Between 1861 and 1865, there were 144,221 Irish born soldiers in the Union Army, 51,206 from New York, 17,418 from Pennsylvania. Ohio contributed 8,129 Irish born volunteers.

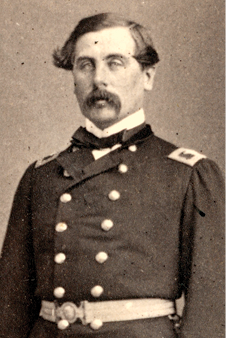

Thomas Francis Meagher

In 1862, a captain named Thomas Francis Meagher became Brigadier General of the fledgling brigade. Meagher was born in Ireland and had been active in the Young Ireland Nationalist Movement until he was apprehended and exiled to the British Penal Colony in Tasmania. He was able to escape in 1853 and made his way to the United States, where he became a well known speaker and activist for the Irish Nationalist Movement.

In 1862, a captain named Thomas Francis Meagher became Brigadier General of the fledgling brigade. Meagher was born in Ireland and had been active in the Young Ireland Nationalist Movement until he was apprehended and exiled to the British Penal Colony in Tasmania. He was able to escape in 1853 and made his way to the United States, where he became a well known speaker and activist for the Irish Nationalist Movement.

Meagher joined the Union Army in 1861, and thought if he could raise an all Irish infantry brigade, the army would have to make him its commander. He could then use the Irish Brigade to bring U.S. support to the nationalist cause in Ireland.

In the spring of 1862, Army officials added a non-Irish regiment, the 29th Massachusetts to the brigade to increase troop numbers before the Peninsula and Antietam Campaigns. In the fall, another Irish regiment, the 116th Pennsylvania Infantry, was added in time for the Battle at Harper’s Ferry.

The Irish Brigade served throughout the war in the First Division of the Second Corps Army of the Potomac. The brigade led the charge in many of the Army of thhe Potomac’s engagements. As a result the brigade’s casualties were disproportionately higher than the rest of the Army of the Potomac. In September of 1862, almost 600 men were killed, in the Battle of Antietam. It is still the bloodiest battle to take place on American soil.

Sixty percent of the men of the 63rd and 69th New York Regiments were lost. All totaled, 22,717 men were killed, wounded or went missing in that battle. Although the Union suffered heavier losses, the inconclusive battle became a turning point for Union forces as they drove Lee and his invading army back.

A few months later, at the Battle of Fredricksburg, 545 of the brigade’s remaining 1200 men were killed or wounded. “Irish blood and Irish bones cover that terrible field today. We are slaughtered like sheep,” wrote one surviving soldier.

Gettysburg

At the Battle of Gettysburg, 320 more of the brigade’s 530 soldiers perished. There is a monument to the Irish Brigade at the site, a green celtic cross with a trefoil, an Irish harp and the numbers of the three New York Infantry Regiments. At the base of the cross is a statue of an Irish Wolfhound, a symbol of perseverence and honor.

Civil War historians cite Gettysburg as the true turning point in the war, leading the way for Union victory, but it was also a turning point for organized Irish involvement in the war. The high casualty rates in the brigade led many Irish soldiers and their families to believe that the Army was taking advantage of their willingnes to fight, and that were being used as cannon fodder.

The National Conscription Act passed that same year aggravated the Irish even more. Under that law, every man in the Union between the ages of twenty-one and forty-five were eligible for the draft lottery unless he could hire a replacement for a three hundred dollar fee. The working class Irish saw this as discrimination against the poor. They felt they were being forced to fight a rich man’s war.

Many of the Irish also believed the reasons for the war had shifted, that it was no longer about keeping the Union entact, but only about abolishing slavery, a cause many of them did not support. In July, one week after the Battle of Gettysburg, thousands of Irish took to the streets of New York. For five violent days they protested the draft laws and viciously attacked any black person they came across, blaming them as the reason for the war.

Black homes and businesses were looted and burned. Stores owned by sympathetic whites suffered similar fates. Federal troops were sent in to quell the chaos and restore order. At least one-hundred and twenty people, mostly African-Americans were killed.

The end of organized Irish involvement in the Union’s cause was at hand. The Irish Brigade was reduced in numbers and disbanded in 1864. Individual Irish volunteers continued to serve with distinction throughout the Civil War and after. Without the heroic efforts of the Irish Brigade, the outcome of America’s Civil War may have been different. It can sometimes be difficult to understand the thinking of men who lived in a different time and circumstance but you can not deny the bravery that was displayed in battle after battle by the soldiers of The Irish Brigade.

Thomas Francis Meagher became the Acting Governor of the Montana Territory after the war. He drowned in the Missouri River in 1867.

For more Information on Meagher, I suggest the book, “The Irish General,” by Paul R. Wylie. An interesting book about the origins of the war, “The Dogs of War 1861,” by Emory M. Thomas. And “Frederick Douglass Selected Works”

Thank you to all our veterans.

*Bob Carney is a student of Irish language and history and teaches the Speak Irish Cleveland class held every Tuesday at PJ McIntyre’s. He is also active in the Irish Wolfhound and Irish dogs organizations in and around Cleveland. Wife Mary, hounds Rían and Aisling and terrier Doolin keep the house jumping. He can be reached at [email protected]

Monthly newsmagazine serving people of Irish descent from Cleveland to Clearwater. We cover the movers, shakers & music makers each and every month.

Since our 2006 inception, iIrish has donated more than $376,000 to local and national charities.

GET UPDATES ON THE SERIOUS & THE SHENANIGANS!